By Stephen D. Bowling

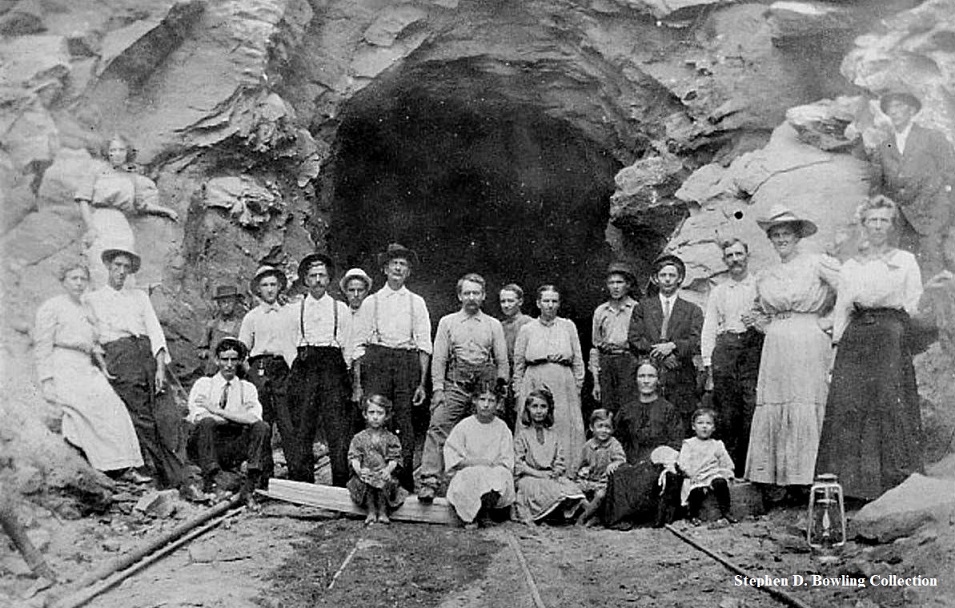

September 19, 1911 – Workmen cleared away the debris from the last blast and reached through the small opening to shake hands with the crew on the other side. Several men crawled through the small opening with smiles on their faces. They were the first to make it through the tunnel, which took nearly six months to complete. They would widen the opening over the next few weeks and lay railroad tracks. Tradition holds that the first train ran through the tunnel on September 19, 1911. The Nada Tunnel was officially open.

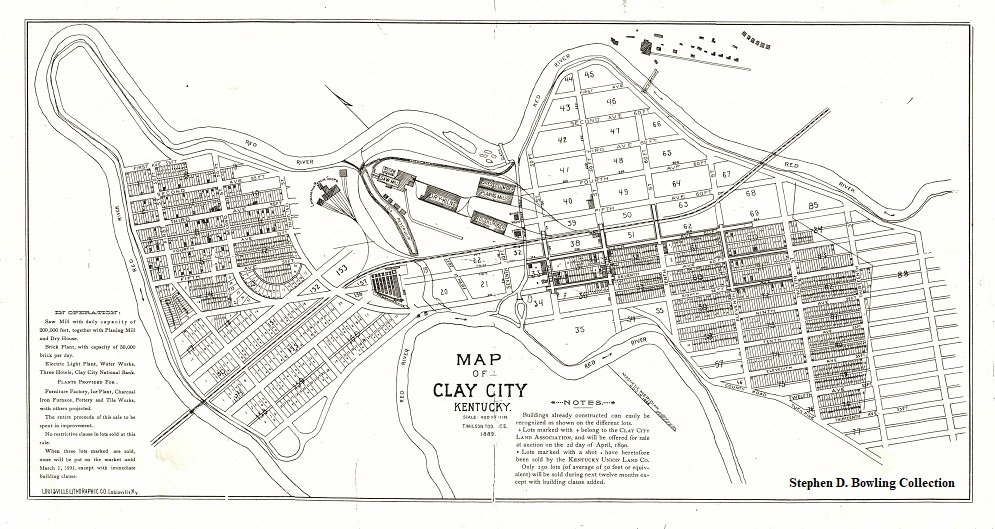

In September 1906, the Dana Lumber Company was created by James A. Flynn in Charleston, West Virginia. In 1910, he formed a partnership with Earnest A. Simmons, and together, they purchased the rites to a large tract of standing timber in the Red River Gorge for $60,000. The expansive acreage was very remote, and no roadway existed to extract the timber for transportation on the Lexington & Eastern Railway line.

As the Dana Lumber Company chief engineer, Simmons surveyed and identified a narrow rib of stone that could be tunneled through to open the Grays Branch valley to a narrow-gage railroad line. He drew up his plans, and the Dana Board of Directors agreed to finance the boring of the tunnel, which was about 6/10th of a mile “up Moreland” from the Nada Junction on the L&E.

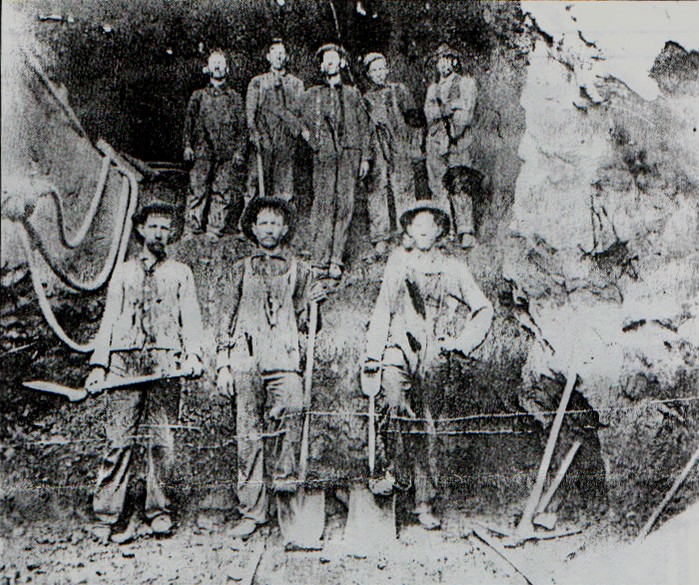

Swift & Weaver Construction Company won the tunnel contract and set to work in December 1910. The planned tunnel connected the Moreland Branch and Grays Branch watersheds to access the timber and natural resources. Construction started in December 1910 as workers built a road and cut trees to gain access to the sandstone cliff. Nearly 800 feet of sandstone lay between two work teams as work started at the head of Moreland Branch in January 1911.

S. A. Simmons drilled the first hole on the west end of the tunnel with a diamond-pointed drill. On the opposite side, C. C. Fletcher of Menifee County drilled the first hole as the two crews worked toward each other, hoping they would meet in the middle. Over the next five and a half months, workers used steam drills and tools to open the shaft and blasted away hundreds of thousands of yards of debris with regular dynamite shots through the tougher-than-expected sandstone.

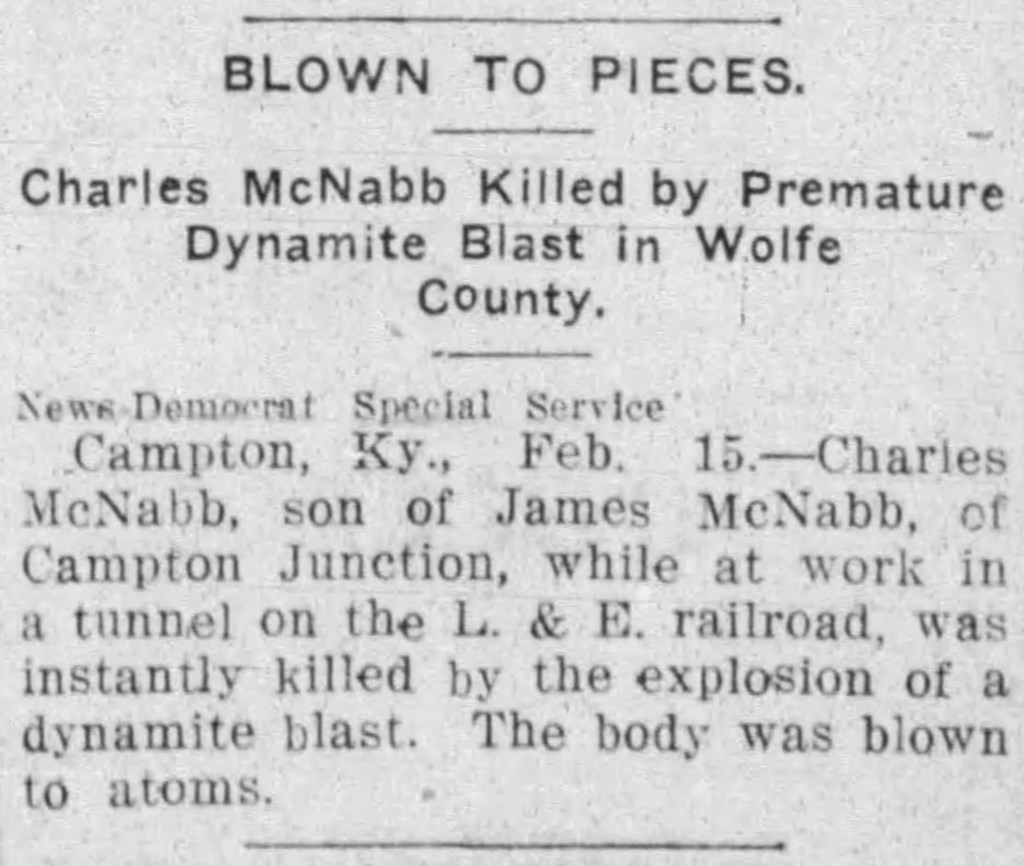

Only one accident happened during the dangerous construction of the tunnel. In February 1911, cold weather settled into the Bluegrass, and heavy snow fell. Crews took a few days off and returned to work at the tunnel on February 14. Crews discovered that their dynamite had frozen solid and would not fire. Charles McNabb, the 19-year-old son of James McNabb, decided to place two sticks of dynamite next to the fire to thaw. The sticks exploded, killing him instantly. Newspaper accounts printed across the state described what searchers found inside the tunnel as a horrific sight, with the body having been “blown to atoms.” Pieces of McNabb’s body were located some distance away from the mouth of the tunnel.

Work continued after the deadly explosion, and crews completed the 12 by 12 opening through the mountain in late July. In 1930, a former official with the Dana Lumber company told The Clay City Times, “They hammered and drilled for 5 ½ months without an engineer hoping to meet at the right place. When they drilled through, much to their delight and the company who was having the tunnel made. When the last shot was fired, the opening was exactly where they wanted it and could not have been done better by an experienced engineer.”

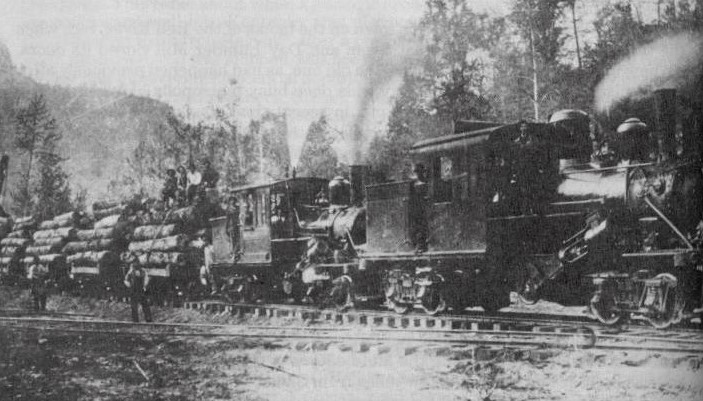

The final work to clear the opening was enlarged and completed in early September 1911. Officials estimated that the tunnel cost $33,000 to construct. Tracks were laid into and extended out the back side of the tunnel into the lush valley below. A log trail was loaded, and the first shipment of Grey’s Branch timber made its way up the tracks to the tunnel. The workers cheered, and the black smoke rolled from the No. 1 Climax engine as it pulled hard up the hill to the tunnel, but the train only made it about halfway through the tunnel before it stopped.

A “high log” on the second car made contact with the tunnel’s roof, and the train wedged firmly in place. Workers used steam drills to clear away more of the ceiling to “unstick” the train. The log was removed, and the first load of timber continued to the big Day Brother’s Lumber Mill in Clay City. Over the next few days, workmen cleared more of the tunnel’s roof to ensure no more trains got stuck. The final tunnel has an average clearance of 14 feet but is taller in some places.

Big Woods, Red River, & Lombard Railroad and the Dana Lumber continued to haul logs through the tunnel over the eight miles of track described as steep and dangerous to the Dana Saw Mill at Nada and the Day Brothers Mill at Clay City. On August 28, 1914, a fire with an “undetermined source” destroyed the large lumber Dana Lumber Company Mill at Nada. The night watchman told company officials the entire plant “burst into flames all over.”

Dana Lumber, whose fortunes had been severely diminished by the cost of the tunnel’s construction and the lack of high-quality hardwoods, collected the $13,500 insurance policy. The policy’s payout was only a fraction of the estimated $20,00 loss and the calculated $30,000 needed to rebuild the mill. Company officials announced they did not plan to rebuild and would finish the contracts with a smaller “circular band mill.” The company and its holding soon went on the market. In November 1914, the Dana Lumber Company sold all its holdings and property rights to the Broadhead-Garrett Company.

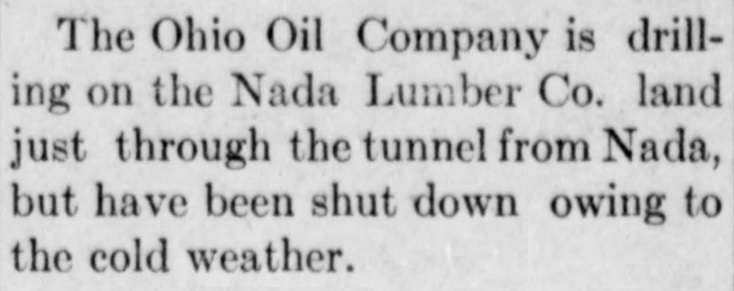

In late 1917, wildcatting crews from several oil companies ventured through the Nada Tunnel to look for drill sites. Large reserves of oil had been discovered to the south and east of the Red River Gorge area, and certain oil lay untapped under the rocky formations of the Gorge. In January 1918, the first oil well was on Gray’s Branch, which was very close to the east opening of the tunnel. Drillers did strike oil, but it was not in a quantity sufficient to sustain long-term operations.

Timber resources owned by the Broadhead-Garrett Lumber Company “played out,” and logging operations ceased in late 1925. In April 1926, Broadhead-Garrett donated the railroad bed and the tunnel to the Powell County Fiscal Court, which turned the gift into a roadway. The tunnel was named the “Garrett Tunnel” in honor of H. Green Garret, who donated the land to the county for public use. The Powell County Fiscal Court accepted the gift and opened the roadway as a connector between the Kentucky-Virginia Appalachian Highway (Highway 15) and the Garrett Highway near Frenchburg (Highway 460).

By early 1926, work crews cleared away many of the loose rocks near the mouth of the tunnel and removed some loose “hangers” inside the dark passageway. Vehicle traffic increased, and James Marat, Routing Manager for the Bluegrass Auto Club in Lexington, became a promoter of the tunnel and the natural beauty that lay beyond the tunnel. Frequent newspaper articles advertised the Garrett Tunnel as a “Wonder to Behold.” Car clubs around the region listed a trip through the tunnel as one of Kentucky’s “Must Do’s” when visiting the area.

Improvements were made to the roadway near the tunnel as tourists visited the area as an extension of a trip to Natural Bridge. The Mari-Nada Road was widened and macadamized with $2,000 provided by the Powell and Menifee County Fiscal Courts to make traveling on the 12-mile roadway more comfortable.

Today, the Nada Tunnel, as visitors commonly refer to it, remains largely unchanged from the original opening blasted out in 1911. Asphalt was later added, and the occasional maintenance work will remove a few loose rocks. The miracle engineering project stands as a monument to determination. The tunnel, known as the “Gateway to the Gorge,” remains a source of amazement to hundreds of thousands who squeeze through its dark and narrow passage to enjoy the wealth of natural beauty and adventure that is Kentucky’s Red River Gorge.

© 2024 Stephen D. Bowling

Thank you for this informative article about the tunnel. My grandfather, Floyd Brewer helped blast out this infamous tunnel. I’ve been through it many times as a child. We used to call it bloody tunnel as the water dripping over red rocks looked like blood.

LikeLike