By Stephen D. Bowling

The day was cold, and the occasional flurry floated through the air.

John Sloan and Eugene Watkins walked slowly around the hill near the Hurst Cemetery on Highway 1812 near the Breathitt-Wolfe County line at about 5:00 p.m. on Saturday, January 27, finishing their grouse hunt. The sun started to sink in the west, and the shadows in the valley were growing longer.

Who saw them first is not recorded, but scattered across the ground were bones that looked almost human. The bones were bleached white and showed bright against the ground when the occasional sunbeam broke through the clouds. Then they saw the skull.

The men made it to a neighbor’s house and called Breathitt County Sheriff Elliott Herald to report their discovery.

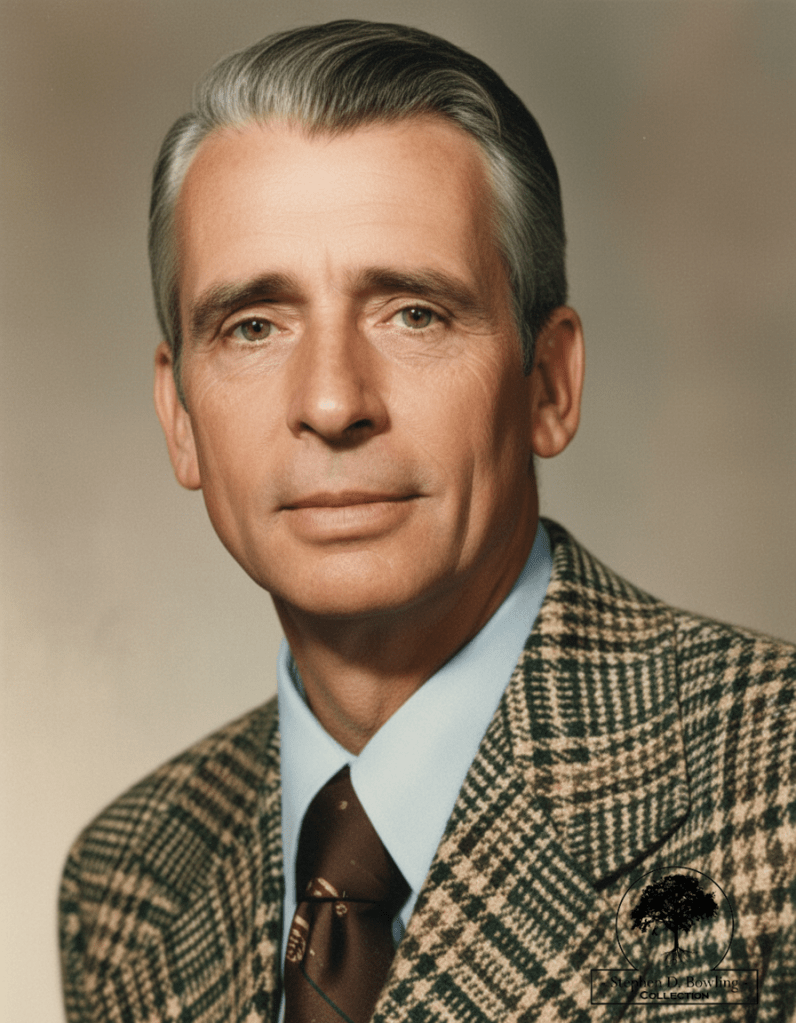

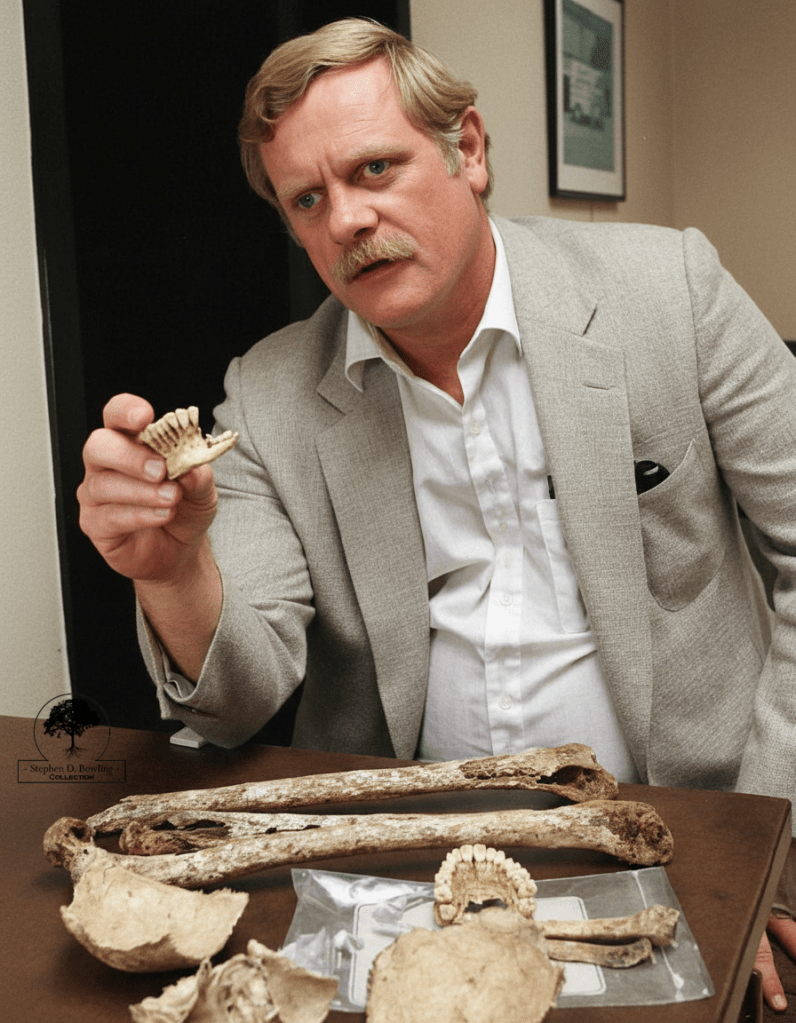

Herald and troopers from the Kentucky State Police drove to the scene and decided to leave the remains in place. Dr. David Wolf, an anthropologist from the University of Kentucky, drove to the crime scene to help collect the remains for analysis.

Wolf and Breathitt County Coroner Dean Spencer determined that the skeleton was from a male about 45 years old, and they estimated he had been there for approximately ten months. No identification was found, and no apparent cause of death was announced. Dr. Wolf collected the bones and took them to his lab in Lexington for analysis.

The following day, he announced that the man was wearing dress pants and a 36-inch belt. “He has had some dental work done,” Wolf told The Jackson Times. “There was no billfold or any papers, or visible labels from the scraps of clothing,” he announced.

The only missing person considered an active case in 1979 was Carl Hollon, who disappeared in 1976. The clothing and estimated height of the man on Frozen did not match Hollon.

In the days before DNA testing, Wolf managed to locate some “body tissue” that “clung to a few bones” and hoped that they could get a blood type from the flesh. They believed the blood type could also help officials identify the man.

By February, the Pathology Department at the University of Kentucky had not issued a report.

The state police also investigated the discovery of the skull of a young woman found in Hyden. Her remains, believed to have been in a field for more than five years, were also taken to the UK Pathology Department for study.

When the report was released, Wolf said the man found in Breathitt County was about thirty-six years old and white. He was believed to be about six feet tall and of “slender build.” He wore bifocal glasses and was left-handed, Wolf said. The only injury noted was a broken nose that had healed.

A study of the bones and evidence at the scene determined that the man had an injury to his leg that had healed, but left the man with a “pronounced limp.” He told reporters that a cane was found near the bones. He found “arthritis-like problems” in the man’s lower back and left leg.

Officials believe that they could see two bullet holes in the clothing, but it was “too deteriorated to determine for certain.”

By August 1979, Wolf had chosen a different direction in his efforts to identify the two sets of remains.

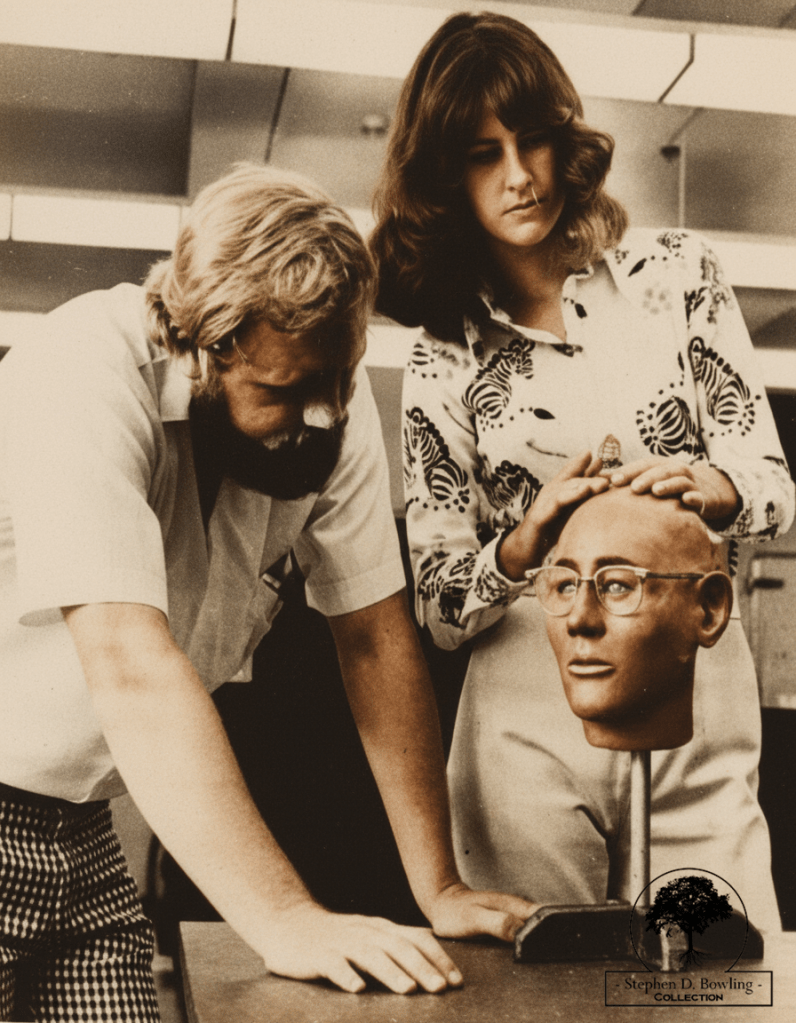

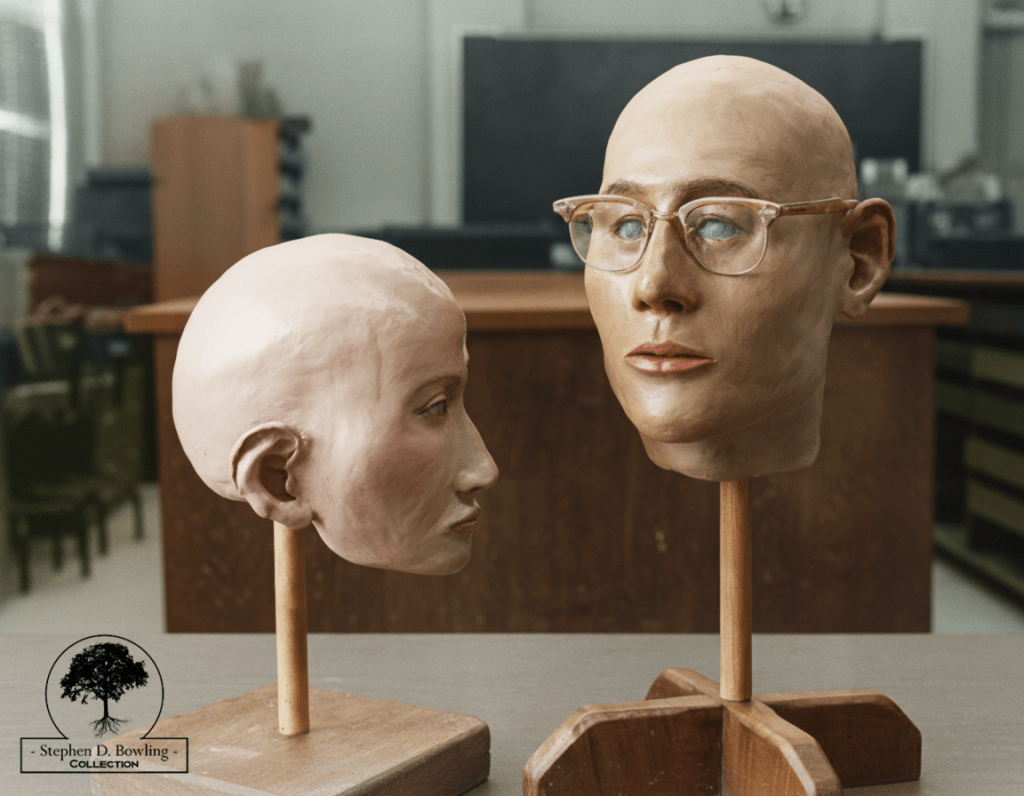

Wolf asked UK graduate student Virginia Smith for help, and together they tried a new technique called “soft tissue reconstruction.” The method had been used for more than fifty years in some investigations of ancient civilization and archaeological work. The process had never been attempted in a criminal case in Kentucky and was untested.

Smith, whose majors were pathology and sculpture, painstakingly reconstructed the faces of the two victims from skull characteristics. She worked for more than 400 hours, meticulously layering balsa wood and modeling clay on the skulls to bring them “back to life.”

On August 1st, the models created by Smith’s work were shown during a press conference at the University of Kentucky in the hopes that they would be identified.

“The story and photos generated dozens of calls,” Wolf said. He was able to eliminate all but two of the names reported as the possible victims.

“We’ve got a couple of possible names, and we’re waiting on medical records right now,” Wolf said. He told Breathitt County officials that he was waiting for medical records from Chicago, Arizona, and the Marine Corps before making any determinations.

Wolf told reporters that he had met with two families, who had viewed the reconstructed head. “They looked at the reconstructions. Both groups of relatives were fairly certain it was a reasonable likeness,” Wolf announced. “Without medical records, I can’t say for sure, but right now everything seems to fit.”

Wolf’s hopes quickly faded. The two requests for medical records went unanswered. The United States Marine Corps refused to share the information in its files. Wolf told reporters that he may have to resort to legal action to get the records he needed.

By October 1979, Wolf announced that he “thinks he has identified the mystery skeletons,” but provided no further clues about the man’s identity.

“If it’s who I think it is, he always carried a lot of money,” Wolfe said. Nothing was found at the scene. He refused to give any further details out of fear that he might “jeopardize the possible future murder trials.”

“We’ve been able to eliminate all but two possibilities for John Doe,” Wolf said. “We’ve narrowed Jane Doe down to one.”

Then the case went cold.

What happened to the bones of the Breathitt County John Doe? He is not mentioned again in the newspaper, and Dr. Wolf never announced his identification. Why would military authorities not share the information they have in an effort to identify the man?

Many questions remain about the case. The State Anthropologist’s Office usually “disposed” of the body after some time by burial in graves marked simply as John or Jane Doe. Academic institutions also frequently requested and retained unidentified skeletons for research purposes.

Three years later, the state created the Kentucky Medical Examiners’ Office to investigate similar cases. David Wolf was appointed the first State Medical Examiner.

So, where is Breathitt County’s John Doe today?

A check with the Kentucky State Medical Examiner’s Office Records Office in January 2026 failed to locate the files for the Breathitt County John Doe (Case 79-F-01). “We may have them,” a spokesperson said, “But they are so old they may have been archived.” The office could not confirm what happened to the remains without the files. Sadly, despite tremendous advances in medical and genetic research, John Doe may remain unidentified.

Despite the lack of a name and a positive identity, his service to science cannot be underestimated. Facial reconstruction is today a common and often successful practice used by medical examiners and investigators. Science-based art, in the days before DNA matching, helped identify hundreds of remains across the country, and a set of remains found on Frozen Creek helped advance that science.

© 2026 Stephen D. Bowling