By Stephen D. Bowling

The four men readied their pistols and pulled the masks down over their faces.

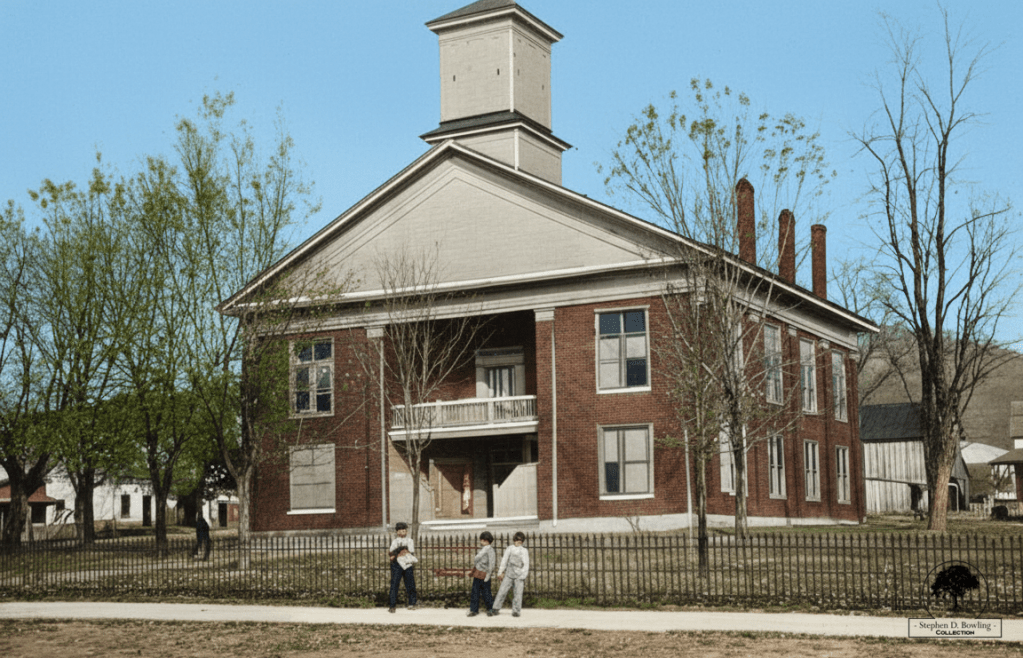

They rushed across College Avenue to the front door of the Breathitt County Jail with guns drawn. The raiding party knocked on the door. One of the men stuck a pistol to the head of jailer Solomon L. “Sollie” Combs shortly after 1:30 a.m. on Christmas morning.

One of the masked attackers grabbed him and “shook him uncontrollably” while demanding the keys to the cells. According to Combs, the men had him “bound and gagged” before he could “make any outcry.”

As Combs lay on the floor, three of the men climbed the stairs to the second floor, where county prisoners were kept, and started searching the cells with a flashlight, checking the twenty-five prisoners held there for one man: Chester Fugate.

The men hit Fugate with a blackjack and hustled him out of the jail into a waiting car.

Lewis Combs, the jailer’s son, was awakened by the noise and ran down the stairs with a pistol in his hand just as the car sped away. He said he fired one shot into the darkness as the car sped down College Avenue and turned onto Quicksand Road (then Highway 15).

Wednesday, December 25th, was cold and snowy. James “Jim” Butler slept in a little on Christmas Day. He got up and stoked the fire before heading out to the field to “pull some fodder” for his livestock. As he approached the riverbank field, he heard the moaning of a man in pain intermixed with loud prayers for help. Butler ran toward the sound and found a bloody man in a drain pipe, clad only in his undershirt and one sock, lying in a pool of water.

The man had been severely beaten and shot. Blood continued to pour from his thirteen gunshot wounds and colored the snow crimson red all around the victim.

Butler laid his coat over the man and ran to his home to alert authorities. He returned a few minutes later and built a fire to help warm Fugate. Word came to Jackson of the discovery, and they sent a hearse to pick up the body, believing that he was dead.

When Breathitt County Samuel Jett Cockrell arrived on the scene with several deputies, they were surprised to find Fugate was conscious and talking. A bloodied Fugate was taken to Bach Hospital, where his wounds were treated. Fugate was hit once in the left arm, five times in the right arm, and seven times in the body.

Sheriff Cockrell interviewed Fugate after doctors stabilized him, and he told his harrowing tale.

According to Fugate, the three men dragged him from the Breathitt County Jail at gunpoint. They verbally and physically abused him as they made their way up Old Quicksand Road. The car stopped about six miles from Jackson near the mouth of Watkins Hollow, and the men threw him over the hill.

Fugate told Commonwealth’s Attorney Grover Cleveland Allen that the men, and every man, six of them, shot Fugate multiple times. The men, satisfied their work was completed, removed their masks and kicked and jeered Fugate as they believed he lay dying. They stuffed him into the culvert to help conceal their work.

Officials believed that the temperature difference between the culvert and the outside, combined with the shelter from the wind provided by the recessed hiding place, saved Fugate from freezing to death during the night.

The medical staff at the hospital worked hard to save Fugate’s life. When his health took a turn for the worse, he asked to make a deathbed statement about the attack and was legally declared “conscious of impending dissolution.”

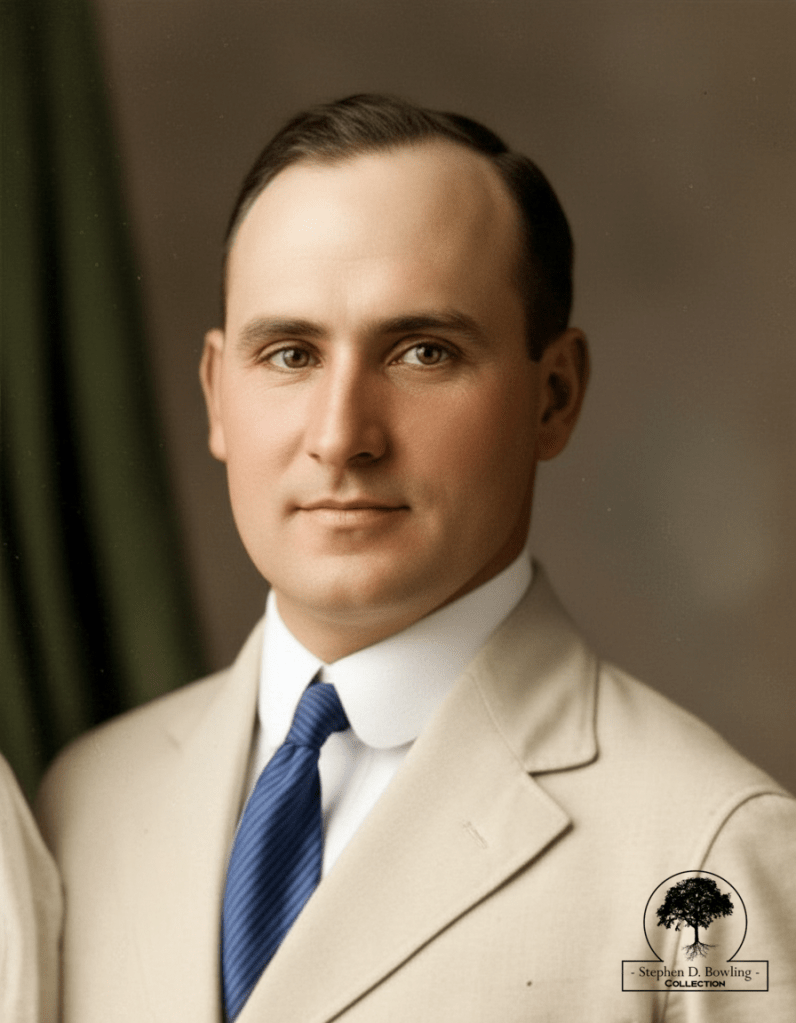

Commonwealth’s Attorney Grover Cleveland Allen, a stenographer, and several other witnesses rushed to his bedside. Dr. Wilgus Bach stood by as Fugate related the events of the early morning hours of Christmas 1929. Unable to raise his right hand due to his injuries, he managed to raise his right index finger while being placed under an oath to tell the truth.

Under oath, Fugate told court officials a story that varied slightly from what he had first told. He said he was asleep when a light woke him up to find L. K. Rice, Benton Howard, and Earl Howard standing over him. He tried to sit up in the bed, and one of the men hit him in the head with a “blackjack.”

He said the men dragged him down the steps of the jail, and there met two more men that he recognized as Sam Watkins and Lee Watkins. “They hit me again with the blackjack and pitched the keys back into the jailer’s room,” Fugate said. He then told of his ride out Quicksand Road.

According to his sworn testimony, the men carried Fugate to the car and threw him in the back seat. L. K. Rice jumped under the wheel to drive, and Lee Watkins got into the passenger’s seat. “Some of the men sat in the backseat, and two or three sat on my abdomen,” Fugate said.

He told Allen that the “injury from the men sitting and trampling on me is causing me more pain than the shots.” Fugate described how the men passed around a bottle and drank “a considerable amount of whiskey.” The men got out, and Rice drove up the road and turned the car around.

The men hit Fugate and rolled him down a steep embankment and shot at him as he rolled. He came to rest at the mouth of the culvert and pretended to be dead. Fugate said that he heard them get back in the car after a few minutes and drive rapidly toward Jackson.

By the time he finished his statement, Fugate was exhausted. He spoke very little the rest of the morning. By noon, his fever spiked, and he was even more delirious. Despite Dr. Bach’s and his staff’s best efforts, Chester Fugate died in the early afternoon on December 26.

The news of Fugate’s death circulated through the community. The investigation into the felony assault turned into a murder investigation.

Fugate was in jail awaiting trial for the murder of Clay Watkins. Watkins was a well-known and well-liked attorney, magistrate, and Chairman of the Breathitt County Board of Education. He owned land near Chester Fugate’s father, Charles D. Fugate, on Rose Branch of South Fork.

Watkins and Fugate met on December 17 to discuss a $4.50 debt that Fugate claimed Watkins owed him after Fugate “raised” some house coal for Watkins. The men did not agree, and a fight ensued. They were separated, and each went their own way. The fight was not the first conflict between the Fugate and Watkins families, dating back to the 1926 killing of Watkins’ brother by Chester Fugate’s cousin, Amos Fugate.

By chance, the two met again on December 18, 1929, at a small store owned by James Clemons just two miles from Jackson. The quarrel was renewed, and Watkins allegedly approached Fugate with a shovel, threatening to kill him. Fugate drew his pistol and fired multiple shots at Watkins in rapid succession, hitting him with three. Clay Watkins slumped to the ground, bleeding profusely with a bullet lodged near his heart, one in his shoulder, and one in the hip.

Family members rushed Watkins to the office of Dr. Myrvin E. Hoge on Main Street in Jackson, and he lived only a short time. Watkins died at 11:30 a.m. on December 18. The L. Porter Ray Funeral Home embalmed the body, and he was buried in the Watkins Cemetery in Snake Valley on December 20, with more than two hundred mourners in attendance.

After he shot Clay Watkins, Fugate fled the scene, but soon realized his life was in danger. From the moment he fired the shot, members of the large and family-protective Watkins Klan had been searching for Fugate. Just hours before Clay Watkins died, Fugate slipped into Jackson and surrendered to the safekeeping of Breathitt County Jailer Solomon L. Combs.

County Judge William Turner and Sheriff Cockrell discussed the possibility of requesting National Guard Troops to ensure Fugate’s safety. Turner decided, after consulting with Governor Flem D. Sampson and Circuit Judge Chester A. Bach, that the troops were not needed and that there would be no assault on the jail. That decision would be questioned after the events of Christmas Day.

Warrants were issued for the men identified by Fugate in connection with the “malicious shooting and wounding,” but the charges were soon upgraded to murder.

The wanted men surrendered themselves, and officials soon arrested Allie Young Watkins, age 16, of Quicksand and Clay Watkins’s son; Lawrence K. Rice, principal of the Breathitt High School and Clay Watkins’s son-in-law; Benton Howard, Deputy Marshal of Jackson and nephew of Clay Watkins; Earl Howard, the Marshal’s brother; and Samuel J. Watkins, Clay’s brother. Another warrant was issued for Lee Watkins, of Hazard, and a nephew of Clay Watkins, who surrendered the following day.

The men appeared in court before County Judge William Turner on December 26 and entered not guilty pleas. All gave surety bonds of $5,000 each, with assistance from Elbert Hargis, Jack Howard, and others, to ensure their appearance in court on the scheduled day.

The Special Breathitt County Grand Jury met on January 6 and did not believe the story of the early morning assault told by Jailer Solomon Combs and his son, Lewis.

Three days later, on January 9, 1930, Commonwealth’s Attorney Grover C. Allen presented a written order from Juvenile Court Judge Ervine Turner waiving the jurisdiction for charges against 16-year-old Allie Watkins. Judge Back accepted the order and “pre-referred” the charges against young Watkins to the Breathitt County Grand Jury, then in deliberation.

A few hours later, the Grand Jury returned several indictments, including charges against eight defendants. Samuel J. Watkins, Lee Watkins, L. K. Rice, Benton Howard, Earl Howard, and Allie Watkins on one count of Willful Murder.

After hearing the testimony and questioning the jail staff about the raid, the Grand Jury included former Jailer Solomon L. Combs and his son Lewis Combs in the indictment, believing they did not “sufficiently resist” the attackers who took Fugate from the jail.

Judge Back issued arrest warrants for both Combses and delivered the writs to James Goff to serve owing to the election for Lee Combs as Breathitt County Sheriff.

The case began working its way through the Breathitt County Court system, but many believed that the defendants could not receive a fair trial in Breathitt County and that an acquittal was likely. By the time the case started in February 1930, the court had decided to assign an elisor to oversee legal service for the case, and Judge Back chose Willard Roark for the job.

After serving warrants and admitting the defendants to bond, rumors started circulating that several defendants were planning to escape to Montana to live with relatives there.

Grover C. Allen rushed into court on February 5 and asked Judge Back to remand all eight defendants to jail to prevent them from traveling. Judge Back agreed, and all eight were settled into the old brick jail on College Avenue.

On the same day, the defense submitted an order requesting a change of venue for the trial. Judge Back reviewed the request and denied the move. After a conference with the prosecution and the defense, Judge Back agreed to obtain a venire of fifty eligible jurors from Estill County to hear the case on February 17, 1930.

Just two days before the trial, Grover C. Allen asked Judge Back to “vacate the bench and not preside in the trial” on “account of the relationship of the Judge to one of the defendants: to-wit: Lee Watkins” based on an affidavit submitted by Adam Stacy with facts about the case. Judge Back adjourned the court without making a decision.

Two days later, on the date of the scheduled start of the trial, Judge Back reversed his decision and granted a defense motion to move the trial to Estill County.

After some legal proceedings, the trials started in Irvine in Estill Circuit Court in early April. John W. Walker, Commonwealth’s Attorney, decided to try the cases individually, and the state announced that they would seek the death penalty against the six active participants Fugate named in his deathbed statement.

The case against Lawrence K. Rice was tried first, and the prosecution presented its case on Thursday, April 8, and rested on Friday morning, April 9. Believing it to be the strongest case, based on Fugate’s statements about Rice entering the jail, the state hoped for a quick conviction, which may signal the course for the rest of the cases.

During the three-day trial, the state called twenty-seven witnesses to prove Rice was a member of the raiding party responsible for Fugate’s death.

The defense argued that Fugate’s alleged deathbed statement was incoherent and coerced. They argued, and a witness stated that Fugate was “in and out of consciousness,” used abusive language, and was combative in his final hours due to pain and heavy doses of medication. The defense attorneys worked to prove that Fugate could not have given the statement that the prosecution alleged because he was “clouded by morphine and pain.” They also highlighted the differing versions of his story.

On April 13, the case went to the jury. After eight hours of deliberation, the jury reported that it could not reach a verdict, and Judge Sam Hurst declared the “case irretrievably hung” as more than 200 observers filled the courtroom. One of the jurors later told a reporter from The Lexington Herald at Irvine that the jury was nine for guilty and three for not guilty.

The rest of the trials went no better for the prosecution. On April 22, four more defendants were acquitted of the murders and released after only forty-three minutes of deliberation. Judge Hurst released the jury and the defendants.

On the sidewalk outside the courthouse, Benton Howard told a reporter that “the people of Estill County are too broad-minded to convict innocent people.”

The acquittal left only the trials of Solomon and Lewis Combs on the docket. On Wednesday, April 25, the Commonwealth’s Attorney Walker filed a motion in Estill Circuit Court to “file away” and dismiss the indictments against Solomon and Lewis Combs and Allie Y. Watkins.

The hung juries, the acquittals, and the final dismissal of the cases brought an end to the Chester Fugate affair. The accused men returned to their lives, and little was said about the case after those cases were closed.

Samuel J. Watkins fathered seven children with his two wives before he died in April 1941.

Thomas Benton Howard and Early “Earl” Howard returned to their families. Earl died in 1939, and Benton followed in 1968.

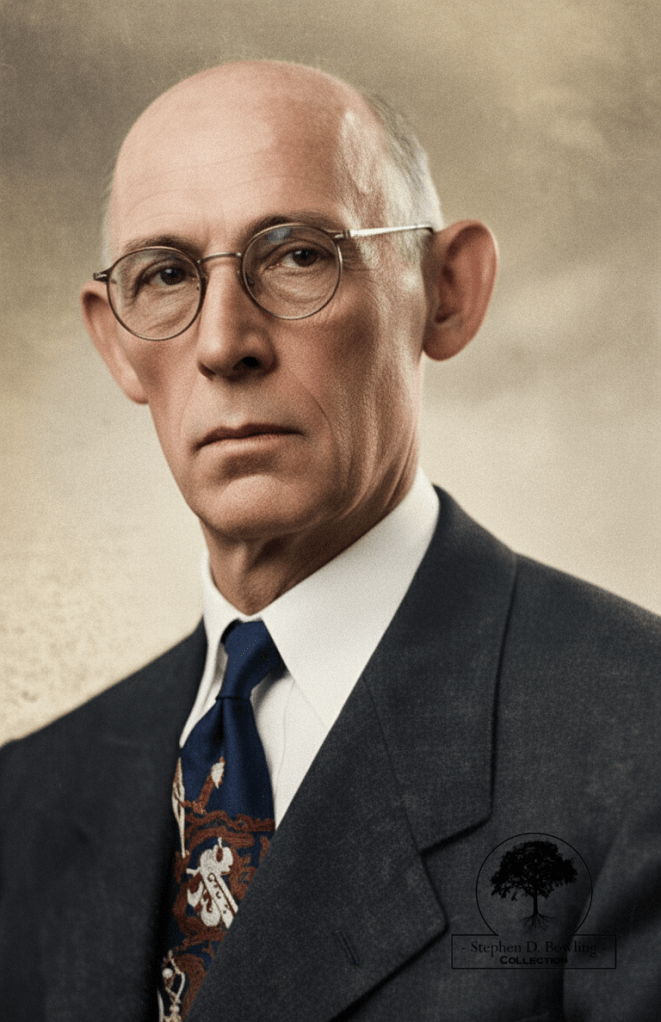

Lawrence Kelly “L. K.” Rice continued as Principal of Breathitt High School. He left Breathitt County and died in 1960 in Louisville. Jesse Lee Watkins died in 1977 at the age of 84.

Allie Young Watkins served several terms as Breathitt County Attorney before he died in 1979.

Solomon Combs never ran or served as Jailer of Breathitt County again after the Fugate lynching. He lived out his life at Lost Creek. Sollie Combs died in 1972 at the Nim Henson Nursing Home.

His son, Lewis Combs, continued in politics and was involved in the bitter fight between the Barkley and Chandler factions in the late 1930s. Lewis was seriously wounded in the gun battle on Main Street in August 1938 that killed his brother, Lee Combs. Two years later, Lewis would fall to the gun of Fred Deaton while the two exchanged shots near the Jackson Post Office on Broadway.

Chester Fugate was buried in the family cemetery on South Fork. The case slowly sank from memory, and the story of the bloody Christmas lynching was nearly forgotten.

Author’s Note: Chester Fugate’s lynching was the second mob action to claim a life in his family. Fugate’s grandfather, Henderson “Hen” Kilburn, was lynched from the bell tower of the Breathitt County Courthouse by a mask-wearing mob on April 9, 1884.

© 2025 Stephen D. Bowling

This is a lot more detail than what I had in my book about the Watkins family.

LikeLike