By Stephen D. Bowling

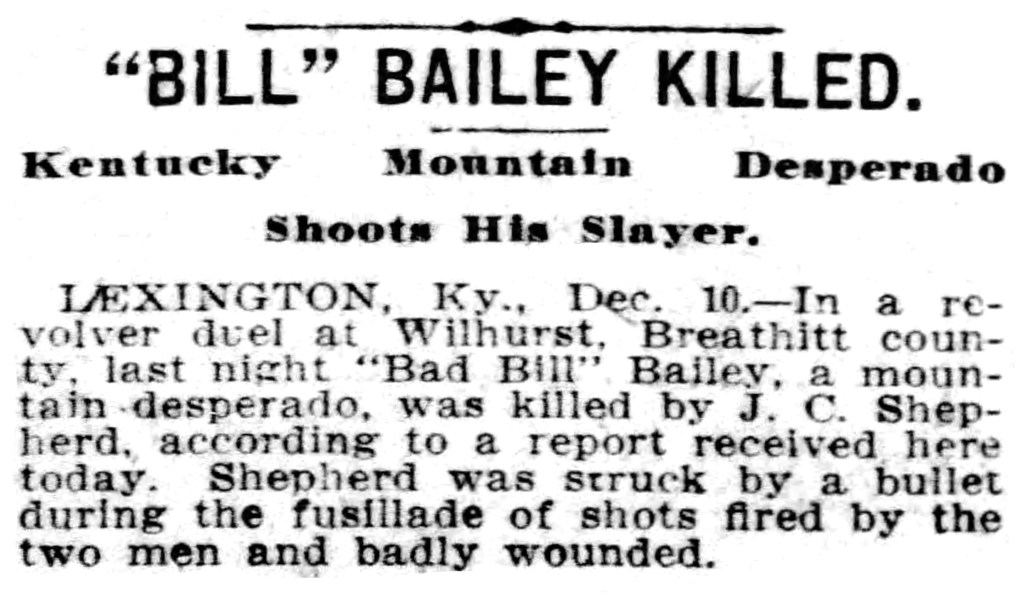

No one cried as “Bad Bill” bled out on the ground outside Shepperd’s store. No one was surprised that he met his end at the wrong end of a gun barrel. It had been expected. No one claimed the body for nearly twenty-four hours. By then, the news of “Bad” Bill Bailey’s demises was on the Associated Press wire to newspapers around the country.

William Bailey was, by all accounts, a “bad man.” He thrived on the traditional recipe of booze, women, and weapons favored by so many community terrorizers. This time, however, he met his match.

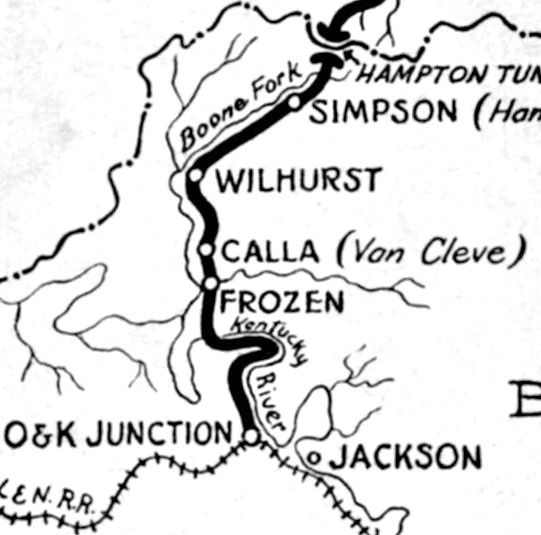

In the fall of 1909, William “Bill” Bailey was near the peak of his “badness.” Often drunk and apt to use his pistol to fire on both man and beast, his reputation proceeded him. Most in the Wilhurst, Calla, and Frozen Creek area learned to avoid him when he was on a “tare.”

On one drunken occasion in September 1909, an enraged Bill Bailey attacked and stabbed John C. Shepperd multiple times in the back with a large knife. Most newspaper accounts of the event noted that Bailey “carved Shepperd up badly.” Shepherd was not expected to live, but over the next few months, he recovered from a wound that “would have killed an average man.”

According to later newspaper accounts, the two reconciled after Shepperd recovered, and there was some peace for some time. At least, there was peace until December 9, 1910.

Just before sunset on December 9, 1910, John Shepperd heard a commotion down the road from his dry goods store near the Wilhurst Station on the O. & K. Railroad. He went to the door and looked toward Calla just in time to see a drunken Bill Bailey walking up the roads toward his store. Wishing to avoid conflict when Bailey passed, Shepperd stepped back into the store. As he watched through the front door, Bailey turned off the roadway and marched toward the store.

Shepperd went behind the counter, and several others in the store moved to one side and stood near the stove. “Bad Bill” tromped up the steps and entered the store. He looked at Shepperd and yelled at the top of his lungs that he was “the bitterest pill that ever trod shoe leather in Bloody Breathitt.” Another witness testified that Bailey shouted, “I’m the worst man that ever saw this place.”

Shepperd believed that Bailey’s announcement was a direct threat to him. Witnesses said that the drunken man reached into his coat “as though he was retrieving a weapon.” Shepperd reached under the counter and took out his pistol, and the two men started firing simultaneously. As Bailey fired, he was instantly hit in the chest. Bailey staggered backward toward the door while emptying his gun at Shepperd.

As he reached the front porch and just before he reached the steps, one of Shepperd’s bullets ripped through the top of Bailey’s head, and he fell out into the yard near the drip of the store. Shepperd fell backward against the wall. When the smoke cleared, Bill Bailey lay dead in the yard as a dark stream of oxygen-rich blood trailed from his skull down through the grass toward the railroad tracks. Storekeeper J. C. Shepperd lay crumpled on the floor with a bullet wound through the side. In all, twelve shots had been fired by the two men, but only three found their mark.

Shepperd contacted the local Justice of the Peace and surrendered. His wound was treated, and he was taken to Jackson and placed in the Breathitt County Jail until his examining trial in the County Court. Judge John Wise Hagins was in Paris testifying in one of the feud trials and could not be arraigned until his return.

Bill Bailey’s body lay in the yard. No one came forward to claim his body, although the news spread quickly. Around five o’clock the next day, neighbors brought a casket and loaded the body.

The Associated Press picked up the report of Bailey’s death and sent it out over the wire to more than 150 newspapers around the country. The many newspapers reprinted a long and flowery editorialized description of Bill Bailey’s death, originally on page 4 of The Louisville Courier-Journal on December 12, 1910.

Bill Bailey’s Home Coming.

“It Is said that Bailey’s- body remained where it fell for twenty-four hours. Bailey, it is said, was decidedly unpopular in the community in which he lived.” – From a dispatch from Jackson.

How Ignominious! Every “bad man” is, in his own opinion, a hero, envied by weaker spirits and admired by the crowd. Such a man, it seems, was Bill Bailey of Breathitt County, whose homecoming is recorded by the Jackson correspondent in a manner that lightens with a touch of grim humor the pitiful tragedy of a causeless brawl with the usual termination.

The title, “Bad Bill,” bestowed by the community in playful recognition of the trait dominant In the character of their fellow citizen, had ministered to the pride of Air. Bailey is a fatuous person who won neighborhood notoriety by being free with his vocabulary, his cutlery, and his shooting irons. He paid for it. In the end, all that could be collected from him by a neighbor acting, as it seems, for the interest of his neighbors. Indirectly, although more immediately in his own behalf and representing, unconsciously, the spirit of retributive Justice, the shadowy protagonist in the drama of catastrophe through which the vain and unreflecting swashbuckler moves toward the inevitable climax.

“Bad Bill” went out upon a bluff. A poker term is permissible in discussing the taking-off of one who made life a game of chance, not wholly unlike the game in which aces and razors sometimes win, where the company is not polite, and in which deuces and savoir-faire compel favorable results where the player is in student of military tactics.

The man whose heart he had once tickled with the point of a knife, in an effort to transfix it, called the bluff when Mr. Bailey, “fortified,” no doubt, with an inferior brand of whisky, as well as armed with deadly weapons, announced, with his accustomed fatuity, that he was the bitterest pill that ever trod shoe leather. His mixed metaphor, which was somewhat worse than his manners, had hardly escaped his lips when the man to whom the information was addressed- a peaceful citizen, by all accounts, who “tended store” six days a week and attended divine services upon the seventh- recognized the exigencies of the moment and began to play a stream of lead upon “Bad Bill,” with intent to deter.

With accuracy of aim becoming the dignity of a sober man of business accustomed to giving methodical attention to matters of detail, the man with the pastoral patronymic- Mr. Shepherd – dispatched Mr. Bailey as a man sitting upon his own front porch smashes the intruding mosquito with one of the works of Lord Byron and calmly resumes his reading.

And the body of “Bad Bill,” who slept well after the passing of life’s fitful fever, cooled in the chaste embraces- of the virgin snow for a day and a night. “Bad Bill” was unpopular in the community in which he had lived. Men of the vicinage were careless of his passing, despite their geographical proximity to the deceased and the neighborly relations they had sustained at some cost to patience- as careless as the remotest stars that illuminated the stillness of the night after the sunset that marked the closing of “Bad Bill’s” last day on earth. No one felt that a hero had fallen. The opinion of the majority was that a nuisance had been abated.

The “bad man” is a sorry figure in contemporary life. As an example of the ill effect of petty vanity and a consuming love of strutting for a little hour or two, the lion of a piece played before a small audience is without a peer. The list of the deluded individuals who have followed the ignis fatuus of bailiwick fame for badness in Breathitt is long. The lives of the majority have been short. Their exploits have been uninspiring. Their end has been ignominious, but history has not recorded the finish of one who died more ingloriously than “Bill Bailey,” who was extremely unpopular in the community in which he lived.

John C. Shepperd, sometimes spelled Shepherd, recovered from his wounds. A strict search of the records of the Breathitt County Circuit Court Clerk’s office did not find his name written with a charge of murder or manslaughter. He did have some civil issues in the years that followed. The large bound volume of the proceedings of the Breathitt County Court after Judge Hagins’ return does not include proceedings against the shooter. It is as though he simply disappeared.

Any information about Bad Bill disappeared too. His grave has not been located and is most likely not marked. No record is known that describes his final resting place. Ultimately, he was a minor figure in the annals of “Bloody Breathitt’s” past. Not much is known of his total body of “rough” work.

Luckily for historians, the newspapers helped ensure that the exploits of one of Breathitt’s “bad men” will live forever.

© 2025 Stephen D. Bowling