By Stephen D. Bowling

November 13, 1912 – The engineer leaned hard on the throttle. The train was already an hour behind schedule as it steamed through the night across Indiana toward Indianapolis. On board the Cincinnati, Hamilton, and Dayton Railway Express were six Breathitt Countians headed for Wisconsin, looking for a new life. They were sure better times lay ahead.

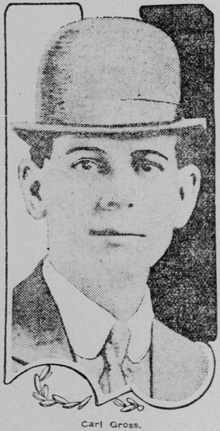

Earlier that day, passenger train Number 36 left Cincinnati and headed for Chicago. The engineer, William Sharkey, asked to have the lines cleared to make his trip faster, and the railroads obliged. When the train rolled into Irvington, a suburb of Indianapolis, he was told the line was open. A few minutes earlier, Carl Gross and several brakemen flipped the switch on the main line and guided a heavily loaded freight train off the main line onto a sidetrack. Gross left the switch and walked down the tracks to make sure the freight had cleared, and the path was free of obstruction. He stepped off the tracks, and they waited for the fast-moving express to pass.

Sharkey was given a “clear track” and planned to “run fast” until he entered the yard limit, where he was required to reduce the train’s speed. Several witnesses were still on the streets, and railyard officials said the train was “making 40 miles an hour.”

John “Bug” Chaney, from Haddix, was probably asleep as the car rocked back and forth on the tracks. His sons, Charley and Clifton, were on board, and Clifton had his wife and children with him. The six Breathitt County residents left Jackson on the Lexington & Eastern heard to Winchester and then to Lexington. At Union Station in Lexington, they purchased tickets on the L.&N. to Cincinnati, where they caught the C.H. & D. bound for Chicago.

According to sources, the group was heading to promised jobs at Pelican, Wisconsin. “Bug” Chaney made several trips to the north in 1910 and 1911. He visited an uncle, William M. Chaney, who moved north after the Civil War to the promise of wide-open land and large stands of timber. John, Clifton, and Charley Chaney had found and contracted “good jobs” at Pelican cutting timber. Clifton brought his young family.

At Lexington, Clifton Chaney considered travel insurance policies for his family’s trip. He walked to the ticket window and talked with a clerk. e was worried that there may be issues with the trip. According to later newspaper accounts, the policy he asked about included a $5,000 accident policy for each of the Chaneys. While Clifton considered the purchase, the clerk was called away by an upset passenger on another train. Chaney could not wait and had to rush without the policies to make his train in time.

The C, H. & D. big engine spewed smoke and sparks into the sky as it barreled through the Indiana night as the Chaneys settled into the Day Car for the evening. Others found a comfortable spot in the Smoking Car as the trip continued. Most were asleep when it happened.

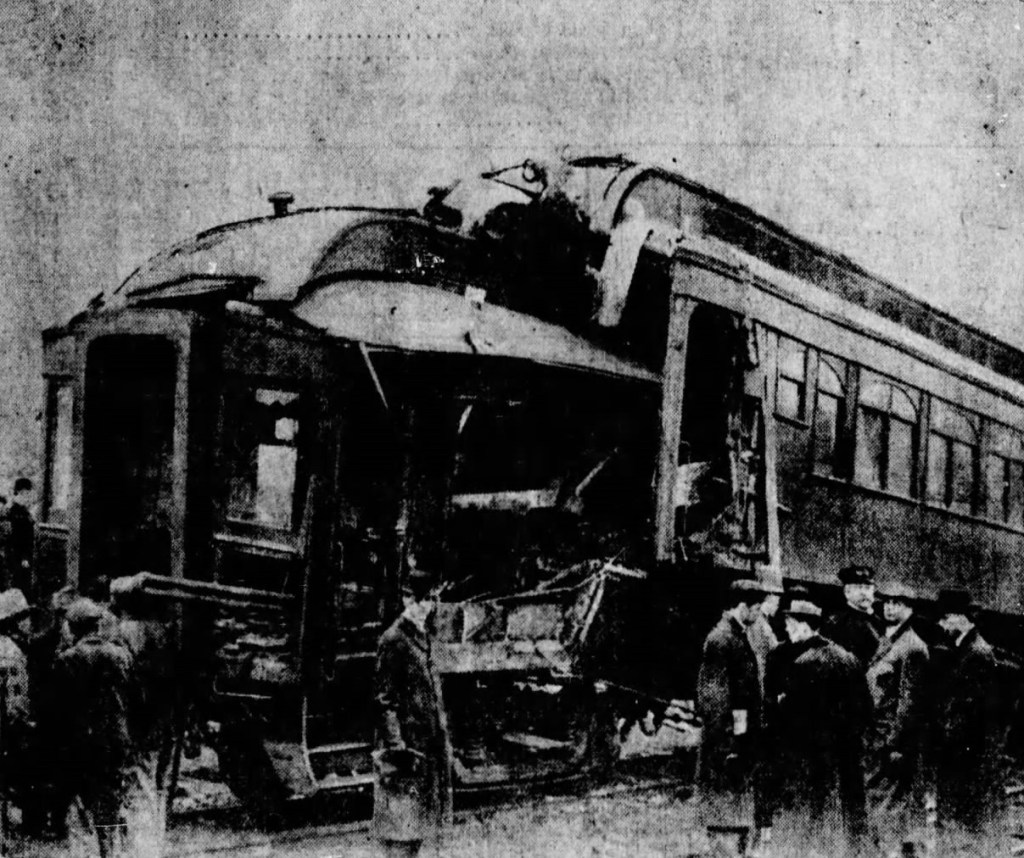

As the train entered the outer limits of Irvington yard, and just as it neared Arlington Avenue, the express took a sharp turn to the right and into the open switch. The engineer and fireman were thrown into the side of the engine’s cab. Engineer Sharkey regained his footing to apply the brakes, but it was too late. The engine of the southbound freight waiting for the passenger train to pass lay directly ahead.

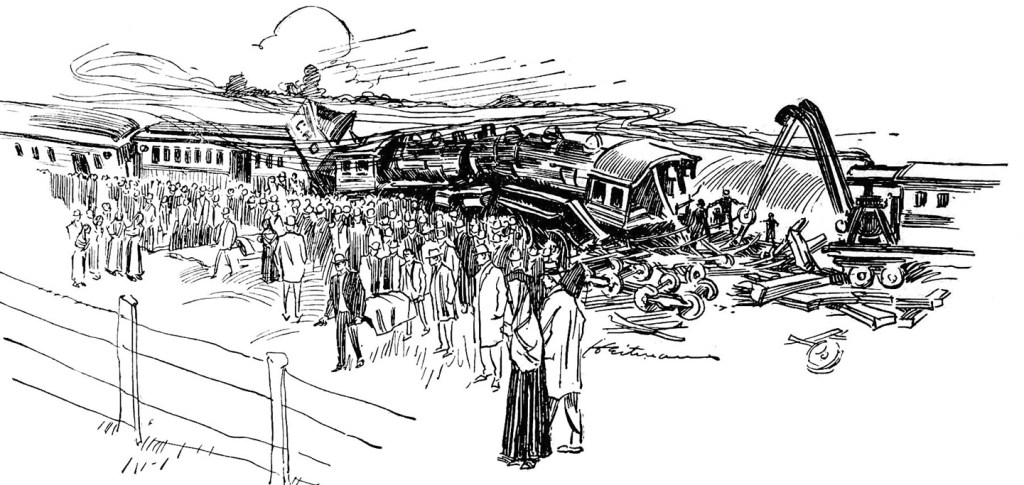

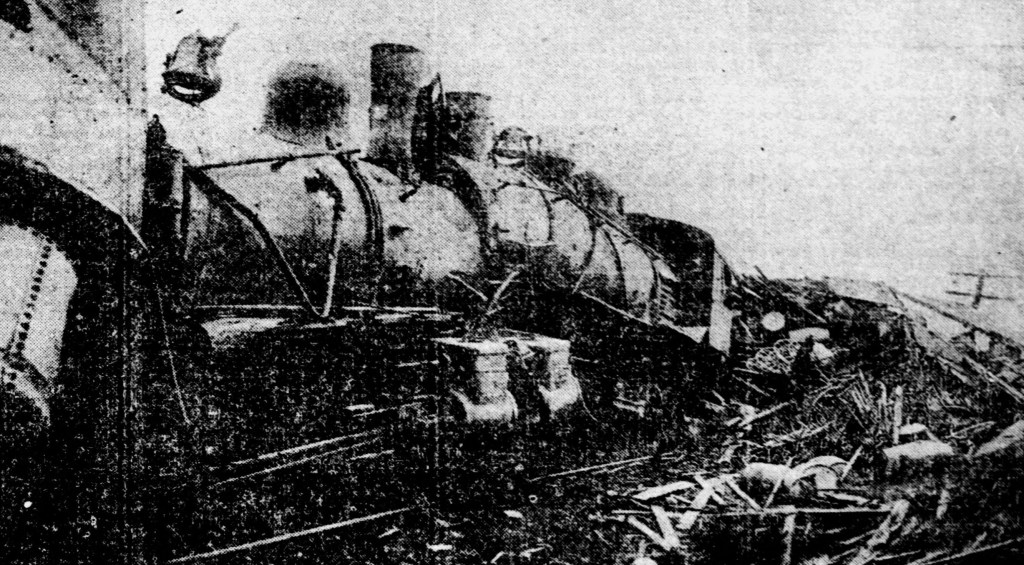

At 3:31 a.m. on November 13, 1912, the two trains collided “head-on.” The sounds of crumpling metal and the crack of wood were heard six blocks away. As a large dust cloud rose from the twisted pile, families who lived along the tracks heard screaming and cries from the injured. The two trains lay in a smoking heap of twisted metal and human flesh.

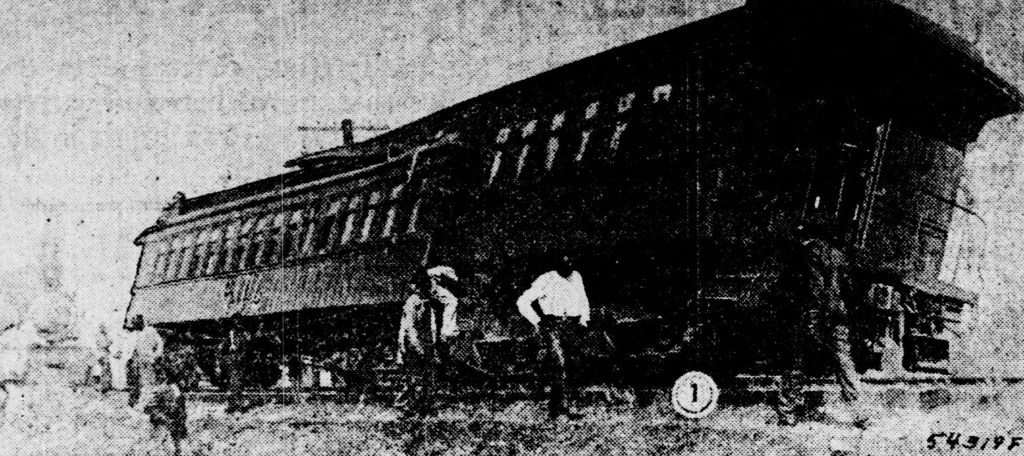

A small fire started in one of the forward cars, and neighbors ran to extinguish the flames before even more were killed. Railroad workers and neighbors ran to the scene. The Day Car and the Smoking Car were telescoped together. When the two engines clammed into each other, the tinder, full of coal, was driven forward into the cab by a steel-reinforced mail car.

Behind the mail car, the weight of four more passenger cars compressed the Smoking and the Day cars into the back of the Mail Car. The Mail Car received little damage, but the other cars were nearly inseparable. Officials would later describe the mail car as a “battering ram” that destroyed the two wooden cars behind it by “telescoping.” The effect of the immense weight destroyed the two cars which were “splintered that very little of them remains intact.”

The cries and screams from inside the two compressed cars were “horrific and soul-splitting.” Neighbors brought axes and started working to cut holes in the sides and top of the cars. They worked non-stop for two hours before they got the first person out. Several of the men climbed down into the cars and started to provide water to the injured they found. Many more lay lifeless, “mangled and torn” from the force of the impact.

Engineer Sharkey was missing. Early speculation was that he saw the crash coming and jumped from the train. Several newspapers reported that he was seen running from the scene “to conceal his guilt in the tragedy.” He would not be found until late afternoon on November 13 when workers and two large cranes separated the engines. His “nearly destroyed” body was found in the wreckage still at the controls, “crushed and scalded.”

Fireman Fred W. Hutchinson, 26, of Madisonville, Kentucky, was injured severely in the impact and then scalded by the exploding boiler and its full head of steam. As he was pulled from the wreckage, he mumbled and was “insensible just repeating the train’s orders.”

Workers cut their way into the Day Car where the Chaneys were found. Charles and his baby nephew, Chester, lay crushed and mangled between two seats. Across the car, the body of Julia (Haddix) Chaney was nearly severed in two and compressed against the side of the car. Her two-year-old daughter, Lillie, was crushed in her arms but, amazingly, still breathing.

John Chaney had been thrown forward in the car and covered by parts of seats and debris. Workers heard him moaning. A doctor removed Lillie from her mother’s arms and handed her through a hole cut into the side of the car. Her breathing became labored, and she was rushed off to an ambulance. John Chaney was extracted and rode to Deaconess Hospital in the same ambulance. Little Lillie Chaney died on the way and was officially pronounced dead upon arrival.

Family patriarch John Chaney lived, despite the projections of doctors, for six hours and died at 9:30 that morning “of crushing Rail Road injuries.” Marion County Coroner Charles O. Durham signed the death certificates for the five Chaneys and nine other victims of the crash. In all, sixteen died, and 16 were injured seriously, while more than 140 reported minor injuries.

By early afternoon on November 13, the Indiana Railway Commission inspected the scene and analyzed the tracks beneath the crumpled wreckage. After an extensive review by the Railway Commission, the Marion County Grand Jury, and several other agencies. Early blame settled on Head Brakeman Carl Gross, who told a reporter immediately after he was hospitalized with a broken leg that he assumed credit for the accident”

“I and some others are to blame,” reportedly Gross said. “I left the switch open and expected one of the other brakemen to close it. The switch was not closed, the wreck occurred, and I am to blame.” Gross later said that he was under medication that they had given him at the hospital when he made his statement.

Clifton Chaney was still alive but seriously injured. He was taken to Deaconess Hospital and was immediately sent to surgery. He spent the next two weeks in the hospital under close medical surveillance. He was told of the fate of his family, and he was able to provide some information for the coroner and directed that the family be shipped back to Haddix for burial.

On November 14, five caskets arrived in Winchester on the L.&N. Railroad. They rested in a refrigerated car on the siding at the Winchester station until the next morning. More than 500 people visited the car and watched as it left for Jackson the next morning.

The train stopped on the opposite side of the river about a mile upstream from the Haddix Depot. Crews unloaded the five caskets and ferried them across the river in a flat-bottomed boat and up the hill to the Haddix Cemetery. Many family and friends attend the burial services on November 15. John “Bug” Chaney, 52, was buried beside his wife, Sarah, who died in 1901. Julia Chaney, 22, was buried a few feet away, nearer to her mother, Sarah Haddix. Charley, 18, Lillie, 2, and Chester, 5 months, were buried beside her.

Clifton Chaney recovered physically. On November 26, Lexington newspapers reported that he passed through Lexington on a train headed home to Jackson. One newspaper reporter noted that he did not look up or acknowledge his question but simply walked heavily on his cane with the assistance of his brother, Seldon Chaney. His father-in-law, John A. Haddix, accompanied Chaney and his hired attorneys, South Strong and O. H. Pollard.

With money received from the claim against the Cincinnati, Hamilton, and Dayton Railway, Clifton Chaney erected new tombstones for his family and his parents.

Workers using heavy cranes cleared the track, working nearly non-stop for the next two days. What they found inside the rubble haunted many of the railroad men who worked the scene. One of the lasting images several talked to reporters about was the sight of something out of place in the tangle of steel and blood.

Seven pieces of pink and white ribbon candy were found on the ground between the tracks in a torn paper sack. During frantic efforts on November 13, rescuers and doctors climbed over the bag and the candy as they worked to recover victims and save lives. Crews dragged the cars away later in the evening of the 14th, and a reporter watched as the steel wheels of the smashed train car pushed several pieces of the candy down into the dirt.

Hours before, Lillie Chaney clutched the small bag tightly as she curled up in the seat beside her father. According to a witness, Clifton Chaney had his arms around her to make sure she did not fall onto the floor as she slept. An injured conductor who passed the spot saw the candy on the ground and told officials, “Here is where the precious little girl was sitting.”

The conductor wiped away his tears and walked away.

The Marion County Grand Jury indicted sixteen railroad officials in January 1913 on a charge of manslaughter for their alleged roles in the tragedy. Most were members of the railroad’s Board of Directors, and several were workmen. Carl Gross was among those charged. After nearly two years of legal wrangling, the court dismissed all charges against the C.H. & D. Board members. The last two indictments, including the charges against Gross, were dropped in December 1914.

Clifton Chaney recovered in Breathitt County and later started a new life at Clay City in Powell County, Kentucky. On March 5, 1915, he married Ethel Martin, and the couple had three children. Clifton suffered from his injuries for the rest of his life. He died on February 21, 1960, and was buried in the Stanton Cemetery at Stanton.

The tragedy of the Chaney family is nearly forgotten in Breathitt County. In Indiana, it is remembered as one of the worst tragedies on the Cincinnati, Hamilton, and Dayton Railway. After the wreck, emergency safety measures were required for every railway in Indiana, and automatic switch signals were installed to prevent another Irvington tragedy. The death of five members of a Breathitt County family and nine others ultimately made train travel safer for others.

© 2024 Stephen D. Bowling