By Stephen D. Bowling

He was running late most of the day. At one of his stops along the way, he was running more than two hours behind schedule. By the time he rolled into Jackson, the entourage of dignitaries and esteemed speakers had shortened their remarks so that the state-wide tour could make up time.

At approximately 1:34 p.m. on October 18, 1920, the Governor’s Special train carrying Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge, the newly elected Republican Vice President nominee, rounded the curve into the Jackson Depot only half an hour late.

Coolidge and his party were only part of the way through their day when the train and its long line of cars steamed into the station at Jackson. Following the Republican Convention, the Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge ticket planned numerous campaign stops. A few weeks before the election, Coolidge announced a 2,000-mile rail swing into Kentucky and beyond.

His train rolled out of Washington, D.C., on Sunday, October 17, and passed through Virginia and West Virginia to Kentucky. Later that night, the train crossed into northeast Kentucky and arrived at Mt. Sterling at 7:35 a.m.

The Kentucky Tour officially kicked off at 9:00 a.m. after Governor Coolidge, Governor Morrow, and the other dignitaries ate breakfast in Mt. Sterling. During the day, the Governor’s Special made its way to Winchester. The party met with local Republican leaders while railroad officials transferred the train onto the old Lexington and Eastern line for scheduled stops at Stanton and Torrent.

Several speakers entertained the crowd at Jackson while the train bearing the special guests barreled up the tracks toward Jackson, trying to make up time. World War I hero Jackson Morris stood at the podium for about half an hour telling the crowd of his exploits when he “faced the German hordes on the fields of Flanders.” As Morris raised his hand to describe the taking of a “Hessian machine gun nest,” a cheer erupted from the crowd as the large, black engine rounded the Panhandle Curve and roared into Jackson.

The crowd began gathering in South Jackson just before the first rays of light made their way over the ridge and down the valley of the North Fork. The numbers grew all day. By 1:00 p.m., observers reported that “there was hardly standing room anywhere near the depot.” Reluctantly, The Jackson Times, widely known as a Democratic newspaper, reported two days later that an “immense crowd surrounded the depot and filled the streets in their eagerness to see and hear the distinguished guests.” However, W. E. Strong, editor of the Times, buried the story on page three. Most reporters from Lexington and beyond were shocked by the turnout in what was considered a “solid Democrat-mountain county.”

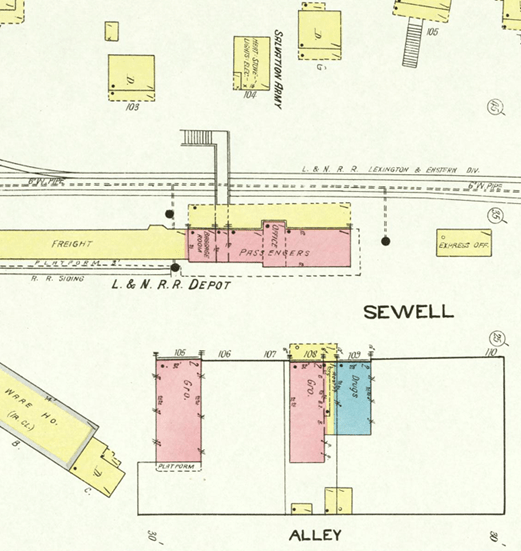

The Governor’s train carrying Coolidge, the newly elected Republican Vice President nominee, halted at the depot and “steamed down.” Onlookers watched from Railroad Street and the walking bridge that crossed the tracks to the Depot to glimpse the number two man on the Republican ticket. Members of the Breathitt County Republican Party met Governor Edwin P. Morrow, Governor Coolidge, Congressman John W. Langley, and their guests on the south platform and welcomed them to Jackson.

Coolidge and the guests shook hands with the 30 or so officials on the platform, including Eli Hall, a prominent Republican and businessman of Viper, who made the trip to Jackson on the morning train to meet the nominee. The entire party walked through the depot to the crowd gathered on Sewell Street (now Armory Drive), where they were met with a “rousing reception.”

Congressman John Langley from Floyd County made a short introductory speech thanking all who had gathered to hear from Governor Coolidge. With little fanfare, Langley called Coolidge to the stand. The man, later known as “Silent Cal,” spoke softly to the crowd for about ten minutes. Governor Edwin Porch Morrow stepped to the podium and started his remarks. The whistle blew, and clouds of steam sprayed from under the train as the wheels began ever so slightly to turn.

He delivered only a few sentences before the train whistle blew again. Morrow waved and ran through the station to catch the train for the next stop in Beattyville. The crowd moved with Governors Coolidge and Morrow to the station’s south side and gave a “rousing good cheer” until Coolidge, standing on the back platform of the train, rounded the curve out of sight.

An unnamed reporter for The Jackson Times wrote that all the speeches were “well received by the people.”

The special train bearing the Republican Vice Presidential nominee on his Kentucky tour rolled north out of Jackson and on to Beattyville, Irvine, Richmond, Lancaster, and Junction City before it stopped for the night in Somerset. At Somerset, the riders on the Governor’s Special were treated to a dinner with area Republicans, and the party rested for the night. The next morning, the train rolled on to Mt. Vernon, London, Corbin, Barbourville, Pineville, Harlan, Lynch, and Middleboro, eventually to Tennessee on Wednesday, October 20.

The whirlwind visit to Jackson marked the first time a nominee for one of the nation’s two highest offices found their way to Breathitt County. Little is recorded about the trip into “Bloody Breathitt,” and no photographs of the visit have been located.

Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge, who ran as “small-government conservatives,” were elected by a landslide, receiving more than 60% of the popular vote. The Harding-Coolidge ticket claimed 404 of the 531 possible electoral votes in an election that saw a 49.2% turnout nationwide. Kentucky, however, did not follow the national trend despite the grand tour of Coolidge. The Commonwealth gave its thirteen electoral votes to the Democrat Party candidate, James M. Cox of Ohio, and his running mate, Frankin D. Roosevelt of New York.

Breathitt County voted for Cox, but the majority was lower than expected. There were definite cracks in the solid Democratic wall in eastern Kentucky, with four of the six counties surrounding Breathitt County sliding over into the Republican column. Despite the Coolidge tour and the rise of Republican sentiment and votes, Breathitt County split over the 1920 election, but it was not the presidential race that caused the trouble.

County voters were divided over the special election of the Circuit Judge for the 23rd District covering Breathitt, Lee, and Estill Counties. The local race pitted two Lee County residents: Republican Samuel Hurst against Democrat J. K. Roberts. When the votes were tallied, local election boards gave the majority of the votes in the district to Hurst, but there was an issue.

One week after the election, official tallies stood at Hurst 6,429 and Roberts 6,224, with one precinct in Breathitt County not reporting its totals. A margin of 205 votes separated the two candidates but within the possible margin of potential votes in the missing precinct. The ballot box for a precinct that usually voted more than 250 and was heavily Democrat had been stolen during a fight at the voting house and thrown into the river. A search for the box in the river found no sign of the missing votes.

The Jackson Times reported on November 12, 1920, that the “election in this county passed off quietly, no one hurt.”

The Circuit Judge’s race was contested by C. C. Turner, attorney for Judge J. K. Roberts. Before the State Election Commission, Turner argued that his client had been “cheated and defrauded” from his “rightful election.” He cited numerous complaints, including the missing ballot box, “terrorized voters,” torn up ballots, vote buying, intimidation, and testimony from one man that he voted at five different precincts. Edward C. O’Rear argued for Hurst that the election was “as fair as one in 23rd District could be.” After hearing from both sides, the Election Commission conferred and issued a certificate of election to Samuel Hurst.

Three years later, on August 2, 1923, President Warren Gamaliel Harding died in a San Francisco hotel of a likely heart attack. Calvin Coolidge, the quiet man who spoke briefly in Jackson on October 18, 1920, became the 30th President of the United States.

Despite the visit of a national political candidate to Breathitt County, the area’s voters continued their support for the Democratic Party. Breathitt County was in the news briefly, and then it returned to its old ways. More importantly, the election reinforced the adage that rather than voting with a focus on national party politics and interests, in Breathitt County, all politics is local.

© 2024 Stephen D. Bowling