By Stephen D. Bowling

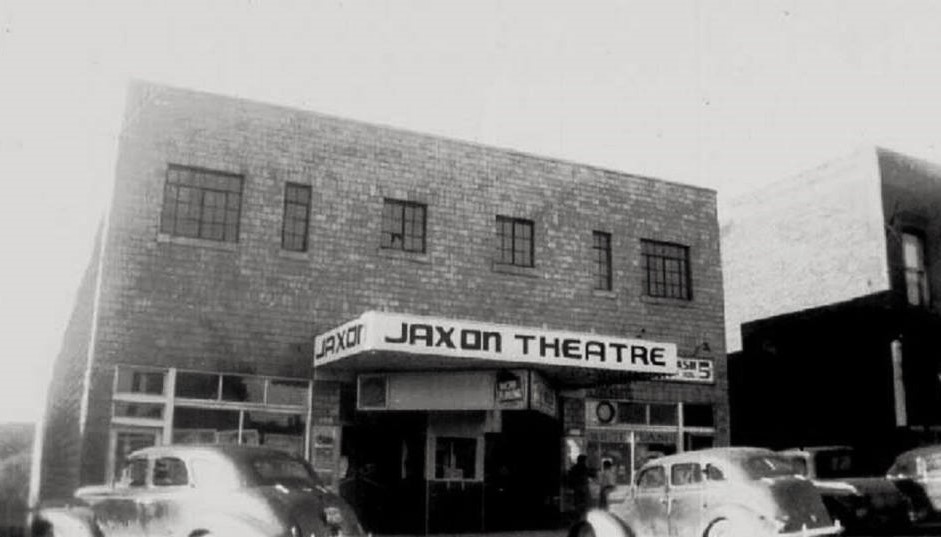

What was it? The rumors circulated hot and heavy around Jackson about the new structure on the Ervine Turner lot on Main Street. Many observers offered their best guesses, but when the large open expanse of the building and the large back wall suitable for the project went up, there were no more questions. The community knew the building would be a new theater for Jackson.

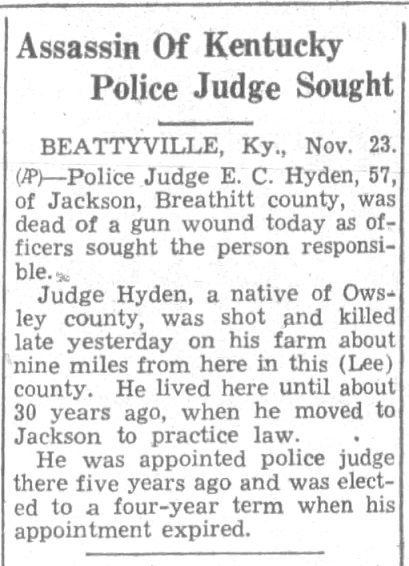

Tragedy helped shape the construction of the building. At 5:00 a.m. on November 22, 1938, Eric Crittenden “E. C.” Hyden, the Police Judge for the city of Jackson, and a driver, Johnny Mullins, drove to Lee County to check on some of his property. In the afternoon, they went to a rental property Hyden owned near the Old Hieronymus Ford in Lee County to collect rent.

A little after 3:00 p.m., Hyden’s renter, 27-year-old Arthur Marshall, told him he could not pay and started screaming at the Judge. A verbal argument ensued over the rent and the division of some “farm goods and corn.” Driver Johnny Mullins, an eyewitness to the events, reported that Judge Hyden turned to go to the car when Mullins pointed a pistol at Hyden’s head and pulled the trigger. Marshall then reportedly fired a second shot into Hyden’s left side. At least two shots struck Hyden, and he died within a few minutes. Later reports and testimony indicated that three shots may have been fired, and Marshall claimed that Hyden advanced on him with a knife. No knife was located at the scene. In March 1939, a Lee County jury convicted Marshall and sentenced him to 15 years in the Kentucky State Penitentiary.

At his death, Hyden owned many lots in Jackson and several pieces of property in Owsley, Breathitt, and Lee Counties. Following his death, his widow, Pearl Abner Hyden, sold many properties to interested parties. On May 13, 1939, Pearl Hyden and Judge Ervine Turner agreed on a price for an empty lot on Main Street opposite the courthouse. After negotiations, Turner and his wife, Marie R. Turner, purchased the lot for $1,505.

The property was described as “mostly level” and extended from the alley between the Day Brothers Building to the Turner property known formerly as the Hargis lots. The deed filed in May 1939 described the property as a lot 119 feet deep and 45 feet and nine inches wide. In 1939, small trees and weeds grew untamed on the vacant lot.

Turner, his wife Marie, and a partner Curtis “Curt” Childers had big plans for this “prime location” opposite the courthouse. Secretly, the partnership had planned to construct a large two-story building. They did not tell anyone its purpose, which made it an object of discussion in Jackson.

Since workers started clearing the site in the summer of 1939, the building’s owners had maintained strict secrecy. Workers began to dig out the foundation and set the first hand-cut stones. The Jackson Times, on November 9, 1939, ran the welcomed verification that a new “movie house” was indeed under construction on Main Street near the Day Brothers’ store. The paper’s writers described the large sandstone building rapidly rising from the stone foundation as a welcome addition to the community.

In 1939, owner Ervine Turner and his business partner, Curt Childers, hired Thomas Sewell as the construction supervisor. Construction progressed quickly on the building, and by March, the walls were up despite snow and cold temperature delays. By mid-April 1940, workers had started adding the decorative brick front to the building. Turner and Childers projected opening day “sometime in the second week of June.”

Delays caused by the weather and supply issues forced Turner and Childers to exceed their budget long before the building was finished. The partners decided to replace their construction foreman with Carl Cundiff, who promised to complete the building as quickly and economically as possible.

Despite Cundiff’s best efforts, the construction was delayed even further while they waited for the delivery of the several large steel beams needed to support the wide expanse of the roof.

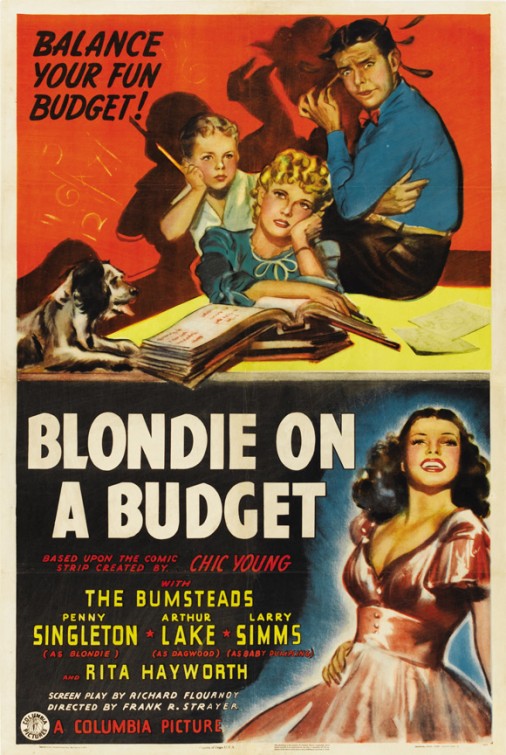

On August 3, 1940, the movie house opened under the working name of the Turner and Childers Theatre with a twin bill headlined by “Blondie On A Budget” starring Arthur Lake and the blonde bombshell Penny Singleton. The second movie on the bill was “Outpost of the Mounties,” an older movie starring Charles Starrett and Iris Meredith. The theater owners also announced that the movie house would feature sports shorts, newsreels, cartoons, and the latest Three Stooges comedy shorts.

The theater operated for several weeks without an official name. On August 15, 1940, Turner and Childers announced a contest. They asked theater patrons to suggest a name for the movie hall. The contest allowed patrons to write a suggested name on the back of their tickets, and the winner was given free admission to the theater for three months.

The suggestion box was soon filled with ideas. Various names were submitted, and several were considered, including The Phoenix Theatre, The American Theatre, and many others.

On September 9, 1940, the name “Jaxon Theatre” was selected from the more than 500 suggestions. Turner announced that Raleigh Moore, a local WWII veteran, was one of the two winners who suggested the variation of Jackson as the name. He took full advantage of his free admission and family members remember him “not missing a single movie for three months. He was there all day, every day, until his pass ran out.”

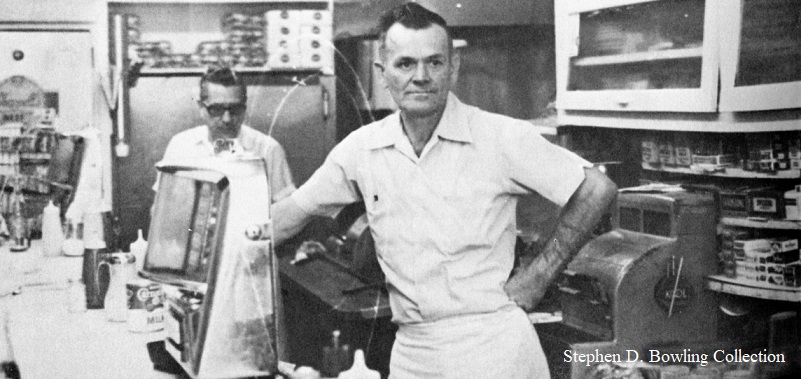

Another business opened in the Jaxon Theatre Building during the first week of October 1940. The new business, a “quick lunch” counter called the White Flash, started serving customers their premier sandwich- the White Flash Burger. The White Flash became known for its fast service and fresh coffee. Various owners of the small restaurant served millions of burgers, and the eatery became a Jackson staple for high school students who went “up town” for lunch. It did not hurt that the lunch counter was close to the courthouse and the infamous Wittler’s (aka Liar’s) Alley.

The Jaxon Theatre used its large performance stage to host a variety of live musical events. In February 1941, Director Homer Arhelger and thirty Jackson City School Band members performed for a capacity crowd before the showing of “Sky Bandits.” Admission for the event was 35 cents for adults and 20 cents for children. Adkins donated $85.00 of the proceeds to the effort to raise funds for the school to buy new band uniforms. Other live concerts over the years included Ralph Stanley, Bill Monroe, other music stars, and local bands. Community rallies and political speeches also found their way to the Jaxon Theatre stage.

Turner and Childers operated the “movies” on Main Street for more than five years. In 1945, they moved on to other financial interests. Ervine Turner focused more on politics, and Childers eyed the coal and timber business. The partners agreed to sell the business to Eric C. Pelfrey, a local businessman who operated several companies in the city. The Turners and Childers reach an agreement with Pelfrey to sell the building for $15,000. The deed, filed on September 6, 1945, transferred the property and the movie business with an exempted easement through the alleyway between the theater and the old Day Brothers Building.

For the next two years, Pelfrey operated the Jaxon Theater and worked to bring the newest releases to Jackson. He made several improvements to the building, including upgrading the restrooms and the upstairs balcony, which was used as a segregated area for African American patrons. Subject to Kentucky laws enforcing racial segregation, the Jaxon Theater continued to use separate entrances and seating areas clearly labeled for “Whites” and “Colored” patrons.

During the years he owned the theater, Eric Pelfrey’s other businesses took off. The theater was successful but profits from his heating and cooling company and especially his appliance business outpaced the movie house. Pelfrey soon was just too busy. He lost interest in the theater, and attendance dropped. Two men approached him in 1947, interested in purchasing the Jackson landmark.

After two months of discussion, Eric C. Pelfrey agreed to sell the business for $6,000 to John S. Hollan and his son-in-law, Crawford Adkins. The January 17, 1947 deed transferred all of the holdings of the Jaxon Theatre to Hollan and honored a signed lease to operate the MRS Market in the “two corner rooms” of the building used to sell “eats and soft drinks.”

The new owners worked out a partnership. John Hollan provided the financial investment needed to purchase the property. Adkins, a trained electrician, brought several years of theater experience to the arrangement. Crawford Adkins married Blanche Hollan in 1938 and lived in Morehead. He relocated to Jackson after a stent in the United States Army during World War Two.

On December 1, 1945, Adkins took over operations at the Pastime Theater on Broadway. Adkins managed the business for Harry Miller following his purchase of the theater from John Bays. After nearly two years of operating the Pastime, Adkins talked Hollan into buying their own movie house. It was a good business model- Hollan managed the money, and Adkins ran the business.

The pair invested in a new ticket booth at the entrance and repainted the theater. New lighting was added to the stage, and new light shined down on the “Coming Attractions” displays near the door. Upgrades and new seating were added for the first time since the theater opened in 1940.

Over the next 16 years, The Jaxon Theatre experienced its glory days under Hollan and Adkins. The movies ran daily and boasted some of the most popular films released by Hollywood. Clark Gable, Betty Davis, Fred MacMurray, Tex Ritter, Fuzzy McKnight, Gary Cooper, Ida Pupino, Frank Sinatra, Shirley McClaine, and hundreds of other Hollywood stars graced the posters outside the Jaxon Theatre.

In 1950, Adkins and Hollan changed the theater business in Jackson by installing air conditioning. The Jaxon Theatre became the first commercial building in the city to install air conditioning to “provide a cool, comfortable atmosphere for theatre patrons during the summer months.” The cold air was provided by two 5-ton Frigidaire units installed by former Theatre owner Eric C. Pelfrey. Adkins flipped the switch on Friday, July 21, 1950, and the big units roared to life, bringing the temperature in the “filmatorium” to 72 degrees. The Theatre would advertise its “Air-Conditioned Comfort” as a major drawing card. Adkins would often have to wake up patrons who took advantage of the comfortable conditions to take a nap.

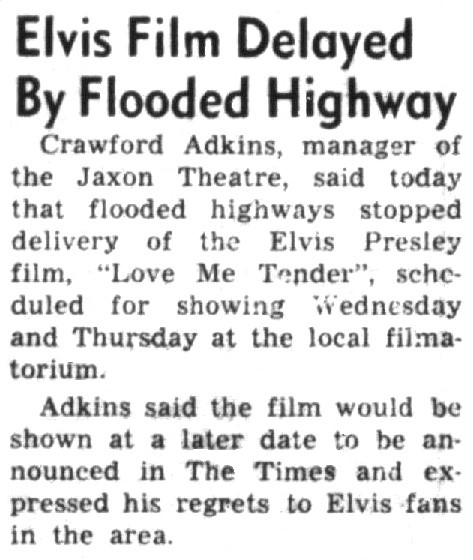

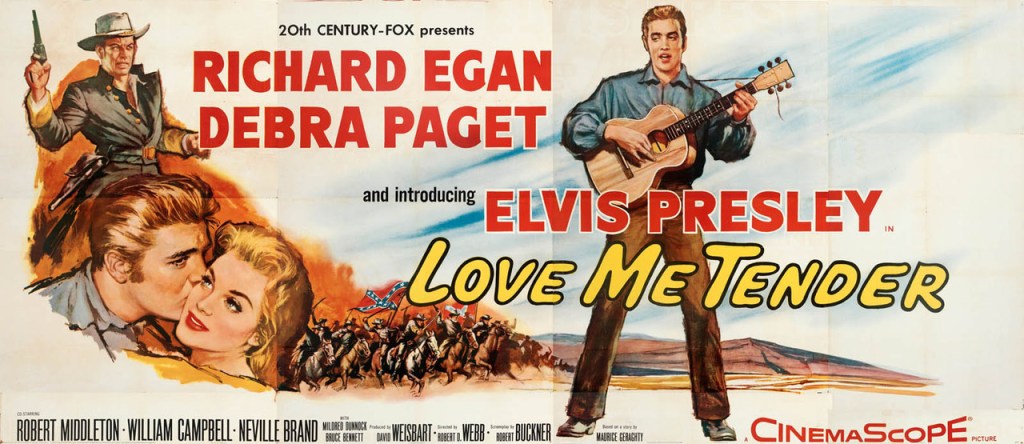

Day after day, the projector rolled millions of feet of film through the Jaxon’s projectors. Saturday morning cartoons, westerns, and afternoon matinees drew large crowds. The weather occasionally got in the way. The highly anticipated showing of Love Me Tender starring Elvis Presley and his hips was delayed by flooding in January and February 1957.

The four film canisters for Love Me Tender finally made their way to Jackson a few weeks after the flood waters receded. Crawford and Hollan announced they would have special showings so that everyone interested in the film could enter the theater. Long lines filled Main Street, and the Jaxon Theatre experienced its best two days on Wednesday and Thursday, March 6 and 7, 1957.

Because of the volume of phone calls that the Jaxon received in the last few weeks of February 1957 about when Love Me Tender would show, Crawford Adkins took an extraordinary step. During the second week of March 1957, a week after Elvis finally hit the screen following the flood, Adkins announced that the Jaxon Theatre would continue its week advertisements in the paper but had added a special phone service. Patrons could call the special number, NO 6-2389, and hear the times and movies that were showing. Adkins boasted that the “What’s On” dial-up service was the first automated answering service ever installed in Breathitt County. Its popularity led to the installation of a “Time and Temperature” feature at First National Bank in November 1963.

Interest in the movies grew, and crowds filled the Jaxon. By 1961, it was showing its age and heavy use. The Jaxon Theatre participated in a city-wide cleanup effort called “Fix-Up-Clean-Up.” The community program helped bring attention to some neglected sidewalks, garbage, and other sanitary concerns. Adkins and the Jaxon joined the effort. In the pages of The Jackson Times, Adkins boasted that the theater had been painted and completely renovated.

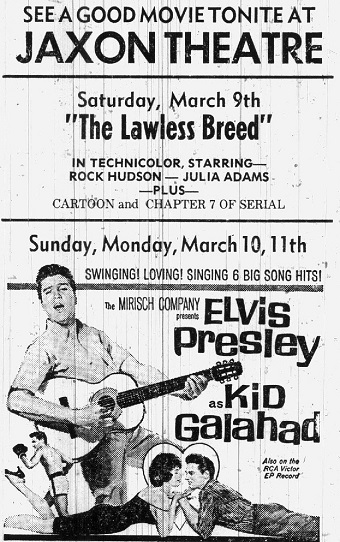

In March 1963, Adkins and the Jaxon Theatre were planning for a big weekend. For weeks, they advertised the coming of another Elvis movie. The new film, Kid Galahad, featured “6 big songs” as patrons could watch Elvis “singing” and “loving” his way through his latest production. The big viewing was slated for Sunday and Monday, March 10 and 11. A Rock Hudson film, The Lawless Breed, played during the matinee on Saturday afternoon. Crawford locked up the theater after it closed and went home to Picnic Hill for the night. It would be the last movie shown at the Jaxon Theatre.

A few hours later, flames were discovered coming from the building shortly after 11:00 p.m. on March 9, 1963. On his return trip from a Hazard basketball game, a Breathitt High School bus driver drove by the building to park the bus in the lot on Court Street and saw the smoke. The fire whistle on the top of City Hall sounded, and volunteers reported to the scene as embers and smoke billowed from the building. Jackson’s only fire truck, a 1949 Ford, rolled up to the scene and hooked to the hydrant across the street.

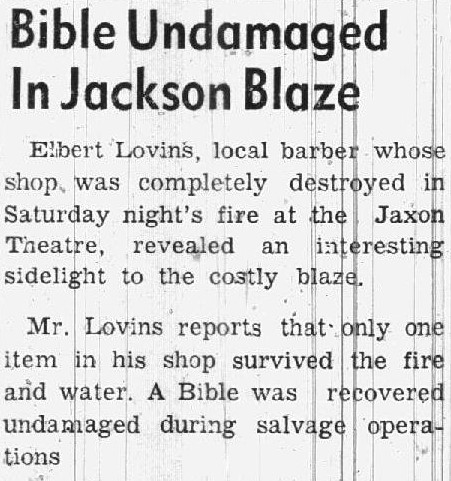

Fifteen volunteers battled the large blaze for over five hours despite outdated equipment and low water pressure in the city lines. Firefighting efforts were also hampered by wire-reinforced windows on the second floor. Without a ladder truck to get water over the exterior walls and onto the fire, police officers used shotguns to blast the windows out of the second story, which allowed firefighters to direct water onto the flames. Despite their best efforts, the interior of the building was a total loss. The White Flash Restaurant and Elbert “Eb” Lovins Barber Shop were also destroyed.

In the days following the fire, Crawford and Hollan debated whether it made sense to rebuild the theater. There was some insurance money but not enough to replace the chairs and screen and reequip the projection room. After some discussion, they decided to use the building for another purpose. Adkins and Hollan chose to remodel the building and turn it into a commercial space.

Plans were developed, and a private contractor was hired to remove all of the fire damage from the interior of the building. Workers hauled away scorched seats, lumber, and roofing materials for the next week. Trucks hauled tons of debris to the outskirts of town and dumped in the city dump on Meeting House Branch Hill.

After ensuring the stone exterior walls were stable, workers started excavating the theater’s ground floor as planned. Tons of yellow clay dirt were removed to build a basement for the building. The crews dug down 16 feet and leveled the floor. Across the street, local workers hired by the Paul Blanton and Associates of Indiana and Acme Wrecking and Lumber Company of Lexington sawed and hammered as they tore away the copper roofing of the old Breathitt County Courthouse. A writer for The Jackson Times pointed out the juxtaposition of the destruction of one building on the south side of Main (the eyesore, as they call it) and the rebirth of another on the north side.

The Jaxon Theatre building, known as the Hollan and Adkins building, rose from the ashes as workmen poured concrete to reinforce the new basement, walls, and substructure. Work on rebuilding the White Flash proceeded, too. The Times announced that the “enlarged and more efficiently designed” restaurant would serve more people and do it more efficiently.

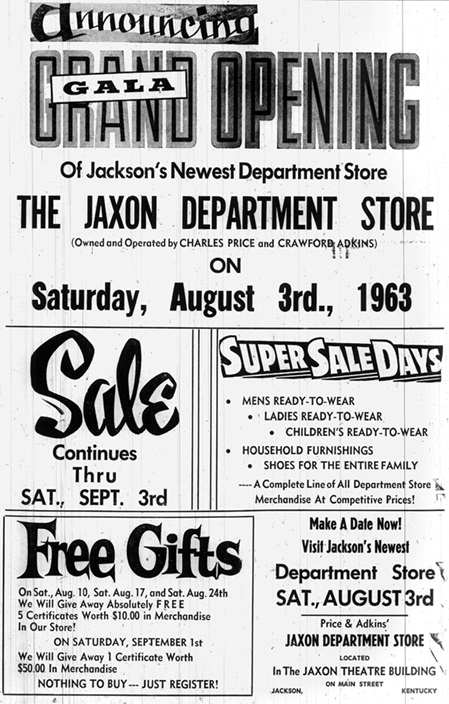

Hollan and Adkins announced that the remodeled building would house a new business formed in Jackson. The new company, owned by Charles Price and Crawford Adkins and named the Jaxon Department Store, planned to operate as a “modern and up-to-date business.” The upstairs area, which once housed the theater balcony, was converted into an apartment. By July 4, 1963, a short article in The Jackson Times announced that work was “proceeding at a rapid pace, with roof and flooring completed.”

Within two weeks, the new White Flash reopened. Diners returned to the brick counter and enjoyed their coffee and meals while the sounds of hammers and saws continued next door. The renovations were completed during the last week of July, and the Grand Opening of the Jaxon Department Store was scheduled for August 3. The new store offered a “complete line of men, women, and children’s clothing and shoes, as well as a distinctive collection of household furnishings.”

Price and Adkins operated their store selling shoes and other clothing to Breathitt County area residents. The store was one of several large mercantile businesses in Jackson, including Rose Brothers, Chapman’s, and the Ben Frankin Store. Competition was stiff, and the store frequently advertised markdowns and sales.

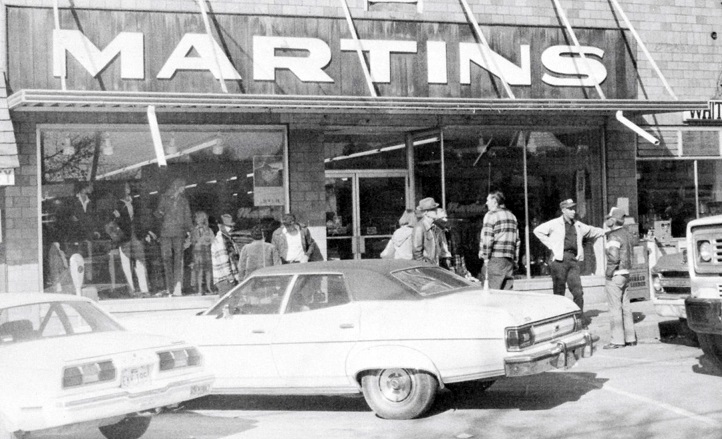

In the summer of 1974, the owners of Martin’s Department Store started discussions with the owners of the Jaxon Department Store about purchasing the Jackson business. The two retailers agreed, and Martin’s assumed ownership of the Main Street store. At the time, Martin’s Department Store operated businesses in “half a dozen towns and cities throughout Kentucky,” with its original store located at Vicco, Kentucky.

The Jaxon Department Store closed to allow Martin’s to “work over the store.” Kenneth Mullins told the community that the new store will offer Bass Shoes, McGregor Suits, Farah Slacks, Aigner leather items, Bobbie Brooks outfits, and many other name-brands due to their associations as a chain store. Martin’s Department Store opened its doors in Jackson on October 4, 1974.

Martin’s Department Store operated in the old Jaxon Theatre building on Main Street for fifteen years. The basement of the building was used for “colorful towels, brightly colored sheets and pillowcases, blankets, bedspreads, and curtains.”

John S. Hollan, a widower, died on March 28, 1981. His three children, including daughter Blanche Hollan Adkins and his son-in-law, Crawford, inherited the building. They kept the building and continued to rent the spaces. The building showed its age and needed some major updating. Rather than invest the funds, the Hollan heirs sold the Jaxon Theatre Building to Douglas and Mary Sue Johnson for $115,000 on November 17, 1986. The Johnsons continued the lease with Martin’s Department Store, and Johnson took over the operation of the White Flash.

As more and more Jackson businesses moved to “the new road,” Martin’s signed a lease with the developers of the newly opened North Jackson Plaza. In the summer of 1989, Martin’s closed their Main Street location and moved the store to a new building near the relocated Jackson Post Office.

The old Jaxon Theatre building went through a series of renters who opened and closed businesses in the commercial space. A few minutes after noon on Thursday, December 9, 1999, a worker in the White Flash noticed smoke coming from the grill area. A worker dropped two pieces of fish in the fryer to fill a customer’s order. Smoke billowed from the grill when she turned around to check on them. “Christine yelled,” owner Doug Johnson told The Breathitt County Voice. “I grabbed the fire extinguisher and sprayed the grill area until it ran out.” Johnson and his staff then helped the restaurant’s patrons out the front door as the flames spread.

The Jackson Fire Department responded to the scene with 17 firefighters and two trucks, including the 150-foot aerial. Fire assistance from the Quicksand and Vancleve Departments helped save the entire block that would most likely have been destroyed had the fire happened one day earlier when all of Jackson’s water system was down for a major repair. “We dodged a really big bullet,” a firefighter said as he rested long enough to drink some water. “If this had been yesterday, we would have been in real trouble.”

Firefighters battled the blaze for more than 4 hours. Smoke managed to seep into the Herald and Herald Law Office next door and into the Citizens Bank and Trust Building, triggering their emergency response plan to secure their facility. Neither structure received fire damage. The apartment above the White Flash, occupied by Nancy Hollan and her son, Alan, was a total loss, and they lost their family pet to the fire.

Doug Johnson told those around him on the sidewalk as he watched the firefighters at work that he would rebuild. Once again, the old Jaxon Theatre Building rose from the ashes in the following months. Johnson died in April 2016, and property ownership was passed to his wife, Mary Sue Johnson.

The White Flash reopened, and the commercial side of the building was used at various times as a furniture store, coin and collectibles shop, restaurant, and several other venues in the years that followed. Most recently, the White Flash expanded into the old Martin’s Department Store side and used the area as a dining room and a concert venue hosting local events and birthdays.

Although the Jaxon Theatre is gone, the memories remain as vivid as the bright colors and scenes that once lit up the screen and inspired the dreams and imaginations of generations of Jackson movie-goers.

© 2024 Stephen D. Bowling