By Stephen D. Bowling

Generations of Breathitt Countians lived their lives in servitude. The unseen populations of African slaves toiled on the hillsides on the banks of the Kentucky River. For the most part, their lives have sadly been forgotten.

Luckily for historians and genealogists, the United States Census Bureau started collecting information on persons held in bondage during the seventh decennial census of Americans in 1850. The census included the regular collection of information on white families. The 1850 Census, and later the 1860 Census, included Schedule 2- Slave Inhabitants. The census was taken to gauge the number and age of slaves in the United States.

In Breathitt County, Census taker John Hargis made his rounds throughout the county gathering information about the people on census day- June 1, 1850. His work took him several weeks, and he finalized and submitted his tallies on October 3, 1850. Hargis reported 3,785 white inhabitants and 170 enslaved residents. By the 1860 Slave Census, enumerator James D. Markham reported 4,980 white residents and 190 black slaves.

Three years later, in 1863, Abraham Lincoln’s execution action freed the slaves in most states in the Union when he signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Fearing the backlash from slave owners, he did not include Kentucky and several other states in the Proclamation. The close of the Civil War and the subsequent passage of the 13th Amendment on January 31, 1865, ended slavery in the United States. Kentucky and several other southern states did not officially pass the amendment in the state legislature until March 16, 1976. Only Mississippi took longer to pass the Amendment in 1995.

Slaves left their plantation homes and farms where they had been held and moved primarily north. In the South, post-war laws, known as the Jim Crow Laws, restricted the movement and actions of African Americans. Slowly, the generational stain of African slavery started to fade as many whites attempted to ignore its painful past, and many former slaves, who had stories to tell, lacked a voice to record them.

In 1936, the Federal Writer’s Project sent workers out into the streets of America to find and record the stories of former slaves. The project’s stated goal was to record for history the “members of the last generation of people to experience slavery” because they were “reaching the end of their lives.” Historians worried that the generation of slaves freed by the bloodiest internal American conflict would pass, and their stories would be lost. The Federal Writer’s Project stressed an “urgency to record their recollections.” It became the largest project of its type in American history to that point.

Over the next two years, the writers fanned out across the country and interviewed more than 2,300 former slaves in 17 states. The final product, when compiled by the Works Progress Administration, numbered more than eighty thousand pages of interviews and hundreds of photographs.

In Breathitt County, they identified three living slaves (although there were more than ten living) in 1930. Writer Margaret Bishop talked with all three, but only Scott Mitchell, a transplanted former slave, was willing to talk on the record about his experience.

Mr. Scott Mitchell’s interview comprised one single page; it is printed here as recorded. The original words spoken by Mitchell are unchanged and may be offensive to some readers- but they were his words.

Breathitt County

(collected by Margaret Bishop)

As told by Scott Mitchell, a former slave:

Scott Mitchell, claims his age as somewhere in the 70’s, but his wool is white on the top of his head. Negroes don’t whiten near as quickly as white people; evidently, he is nearly 90, or there-a-bouts.

“Yes’m I ‘members the Civil Wah, ‘cause I wuz a-livin’ in Christian County whah I wuz bohn, right wif my masteh and mistress. Captain Hester and his wife. I wuz raised on a fahm right wif them, then I lef there.

“Yes, Cap’n Hester traded my mother an my sister, ‘Twuz in 1861, he sent em tuh Mississippi. When they wuz ‘way from him ‘bout two years he bot em back. Yes, he wuz good tuh us. I was I wuz my mistess’ boy. I looked afteh her, en she made all uv my cloes, en she knit my socks, ’cause I wuz her niggah.

“Yes, I wuz twenty yeahs old when I wuz married. I members when I wuz a boy when they had thet Civil Wah. I members theah wuz a brick office wheah they took en hung colored folks. Yes, the blood wuz a-streamin’ down. Sumtimes theah hung them by theah feet, sometimes they hung them by theah thumbs.

I cum tu Kentucky coal mines when I wuz ‘bout twenty years old. I worked at Jenkins. I worked right here et the Davis, the R.T. Davis coal mine, en at the Bailey mine; that was a-fore Mistah Bailey died.

When I worked for Mistah Davis he provided a house in the Cut-Off, that’s ovah wheath the mine’s at. We woaked frum 7 o’cllock in the mawnin’ til 6 ‘clock at night. Yes, I sure liked tuh woak for Mistah Davis. I tended fushnaces some, too. I sure wuz sorry wen Mistah Davis died.”

Library of Congress, WPA Slave Narrative

According to sources, Scott Mitchell was born in Christian County, Kentucky, in 1857. He was the son of Adeline Hester, an enslaved house servant, and Frank Mitchell, an enslaved field hand. Another source stated that Scott Mitchell’s father was his mother’s master, Mr. Hester. No reliable source exists to substantiate either.

Mitchell was raised on the Hester farm in Christian County. According to Mitchell’s account, his mother and sister were sold in 1861 but later purchased and returned to the Hester Farm. As is customary with slave biographies, little is known about his early life other than the details he provided in his narrative.

When Mitchell was freed at the war’s end, he moved to several locations, including Hickman County, Tennessee, before he moved to Kentucky. According to his account, he worked as a fireman at one of the blast furnaces in the eastern section of Kentucky.

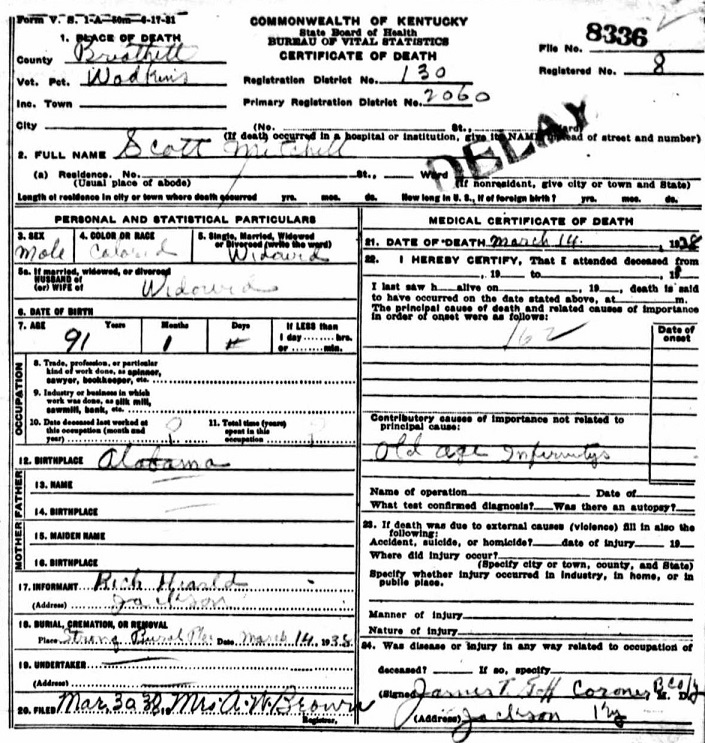

Little is known of Mitchell’s life. No other record of him has survived. He died on March 14, 1928, in the home of Rich Herald in Jackson at the reported age of 91. Coroner James T. Goff identified his cause of death as “old age infirmitys.”

He was buried in the Strong Cemetery on a small swag between Meeting House Branch and Porter Hollow with several other former Breathtit County slaves and their descendants. His grave is not marked.

© 2023 Stephen D. Bowling