July 29, 1944 – William Adkins raised his large family at Elkatawa. He and his wife farmed their land along the Kentucky River to support their fourteen children. In July 1944, one of their sons, William Woodrow Adkins, was killed in action by the Wehrmacht in battle in France near the city of Saint Lo.

The fight for Saint Lo was an important struggle in the American and Allied efforts to secure a foothold in France during the weeks following the D-Day invasion. The battle, which was considered part of the Hedgerow Offensive, sought to capture the strategic city on the Vire River from the Germans who had occupied the town since 1940. For twelve days, the battle raged. American aircraft repeatedly bombed the city, destroying an estimated 95% of the structures.

On July 19, 1944, American forces took control of the city, but sporadic fighting and street-to-street battles followed as the United States Army cleared pockets of Germans for more than two weeks. One of these street skirmishes claimed the life of William Adkins. The number of Germans killed at Saint Lo could not be determined, but American losses numbered nearly 11,000, including Adkins.

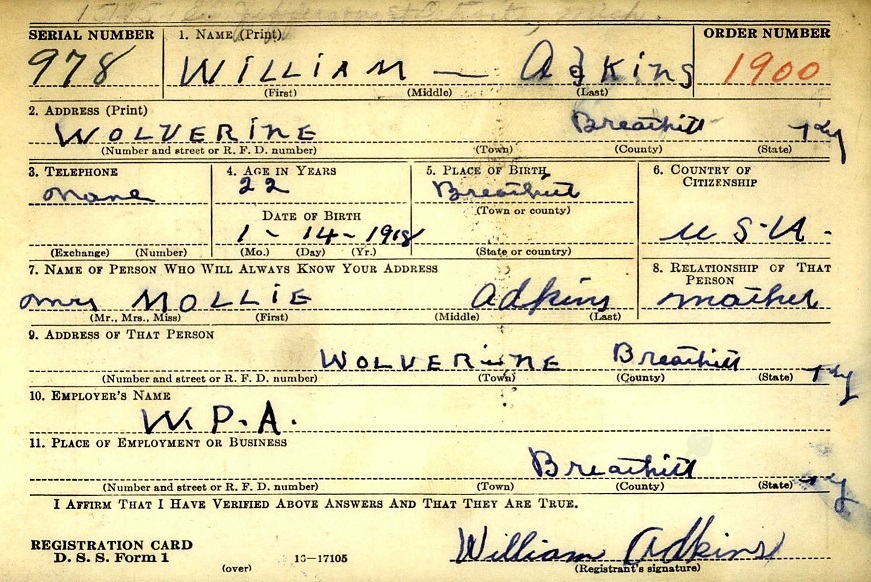

William Woodrow Adkins was born on January 14, 1918, near Wolverine in Breathitt County, Kentucky. He was the fifth son and the youngest of the fourteen children born to William and Mary “Mollie” (Adkins) Adkins. As a child, he was known to his family as Woodrow, but as an adult, he went by William, or more commonly, “Little Bill.” Woodrow attended the Wolverine School and completed the first eight grades.

When the German army invaded Poland in 1939 and after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, William Woodrow Adkins registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, as required. Bruce Cundiff, the Draft Registrar for the Wolverine Precinct, described Adkins as a white male, about five feet and five inches tall. Cundiff reported that Adkins had gray eyes, brown hair and was of a “light complexion.” He did note a scar on the left side of Adkins’ head from a previous injury. At the time of his registration, Adkins, then 22, worked on a Works Progress Administration job in Breathtit County, building roads and culverts as part of the local New Deal effort.

Adkins worked for the WPA until the fall of 1942, when his draft number was selected. He was called to active duty on October 2, 1942. He reported for duty and was mustered into the United States Army on November 11, 1942, at Huntington, West Virginia. He was assigned Army Serial Number 35639457. After basic training, he was assigned to Company D of the 119th Infantry Regiment. The regiment was trained at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and was assigned to the 30th Infantry Division.

On December 7, 1942, the 119th regiment moved to Camp Blanding, Florida in preparation for the move to the European Theatre of the war. The final phase of their training occurred at Camp Forrest, Tennessee. Adkins and the 119th Regiment shipped out to England from Boston on September 4, 1943, in preparation for the planned Allied invasion of France. Their ships docked at Liverpool, England on September 23, and the regiment moved by train to Rustington, Middleton, and Little Hampton in southern England. His regiment landed at Normandy on June 13, 1944, and hurried into battle at their assigned positions along the Vire River. What followed was a long series of running battles, complete with sniper fire from both sides and house-to-house fighting as American and Allied forces fought for every town.

The official records differ on the exact date he was killed. One military source lists the date as July 26, 1944, and another lists July 29, 1944, as the date of death. The official regimental records indicate he was reported as “missing and dead” on August 28. The body was recovered in early August. With full military services, he became the first casualty interred in the American Military Cemetery at Saint Laurent, now known as the Normandy American Cemetery. The United States Army sent a citation and a photograph of his grave to his mother at Wolverine.

To Mollie Adkins, a picture of her baby’s final resting place was not enough. She sent several letters to the United States Army requesting the return of his body. She and her husband, Bill Adkins, visited the local recruiting office above the Jackson Post Office on Broadway. She made numerous requests that her son be disinterred and brought “home to Breathitt County” as soon as possible.

It was her wish that he be buried in the family section of the Hays Cemetery on the hill at Wolverine. The Army recorded her request but informed the family that the return of her son could not occur for some time. The end of the war in 1945 brought her hope that the process of returning William’s body would happen.

Between 1944 and 1947, the stress and worry about the ultimate fate of her son’s remains weighed heavily on her. The family reported that her health rapidly declined, and she developed an “enlarged heart.” For two years, she suffered rapid and uncontrollable increases and decreases in her heart rate. She was frequently tired and unable to perform many of her usual household tasks. On October 14, 1946, she suffered a serious health issue and never really recovered.

She died at home at Wolverine on December 26, 1947, with a picture of her son William W. Adkins on the dresser beside her bed. Her last thoughts were undoubtedly of her son resting so far away in France. The Ray and Blake Funeral Home at Jackson prepared the body, and services were held at the home. She was buried two days later in the Hays Cemetery near a small child she lost in its infancy.

Less than a month later, news came from the United States Army that William W. Adkins’ body would be returned to the family at Jackson in early 1948. The Jackson Times printed a story on February 12, 1948, on the front page announcing the return of Private William Adkins.

Body Of Slain Soldier Buried At Elkatawa

The body of Private William Adkins, who was slain in battle at St. Lo, France during World War II, was laid to rest in the Hays Cemetery at Wolverine last Sunday afternoon after services at Elkatawa.

A son of William Adkins, Sr., of Elkatawa, young Adkins died on July 29, 1944 while serving with the U. S. Army forces during the early battles following the invasion of Europe. His body was first buried in a U. S. Military Cemetery near St. Lo, but was returned here the past week by the War Department at the request of his parents.

His mother died last December after a short illness.

Prior to entering the army, Pvt. Adkins had been employed in Detroit, Michigan.

The funeral service at the Elkatawa church was conducted by the Rev. E. M. Mullins and the Rev. Glenn B. Rhodes.

Survivors, in addition to the father, include two brothers, Ned of First Creek and Matt of Seco; and four sisters, Mrs. Cora Strong of Guerrant, Mrs. Grace Reynolds of Hazard, Mrs. Ruth Combs of Leatherwood, and Miss Florence Adkins of Elkatawa.

The Jackson Times, February 12, 1948, page 1

William Woodrow Adkins returned to Breathitt County on Saturday, February 7, 1948, in a flagged draped casket. His body was unloaded by the family at the Elkatawa station and taken by wagon to the family home at Wolverine. The following day, Sunday, February 8, he was buried, as she wished, with his mother in the Hays Cemetery at Wolverine. On February 16, 1948, Bill Adkins, William’s father, walked to the Elkatawa Post Office and filled out a form to have a military tombstone placed on his son’s grave. The stone arrived and was placed on his grave at the end of April.

William Woodrow Adkins was one of the many Breathitt County soldiers killed during World War II. Not all of them were returned home like William Adkins. Many still lie under the fields of France and Belgium as symbols of the sacrifice Breathitt County soldiers have made for freedom at home and around the world.

© 2023 Stephen D. Bowling

A mothers love is undeniable! Your story gave me chills. So glad he is resting easy next to his family mother. she died to get him home – less red tape from the other side?

LikeLike